The 2/10th Battalion was raised in Linlithgow in 1914 and spent most of the war on coastal defence duties around Berwick. In June 1918 it moved to Ireland and, shortly afterwards, it received orders to move to Russia. By that stage of the war the Battalion was largely manned by soldiers who, although rich in experience, were officially graded as fit only for garrison duty. Similarly many of the officers were spending a six-month period of service at home following long periods of duty in France. Yet, at the end of July, reorganised and reinforced to a strength of 1,000, it left Ireland for Aldershot and, in early August, sailed for Archangel in northern Russia as part of a task force comprising of British, Canadians, Australians, French, Italians and Americans.

2/10 RS march through Archangel

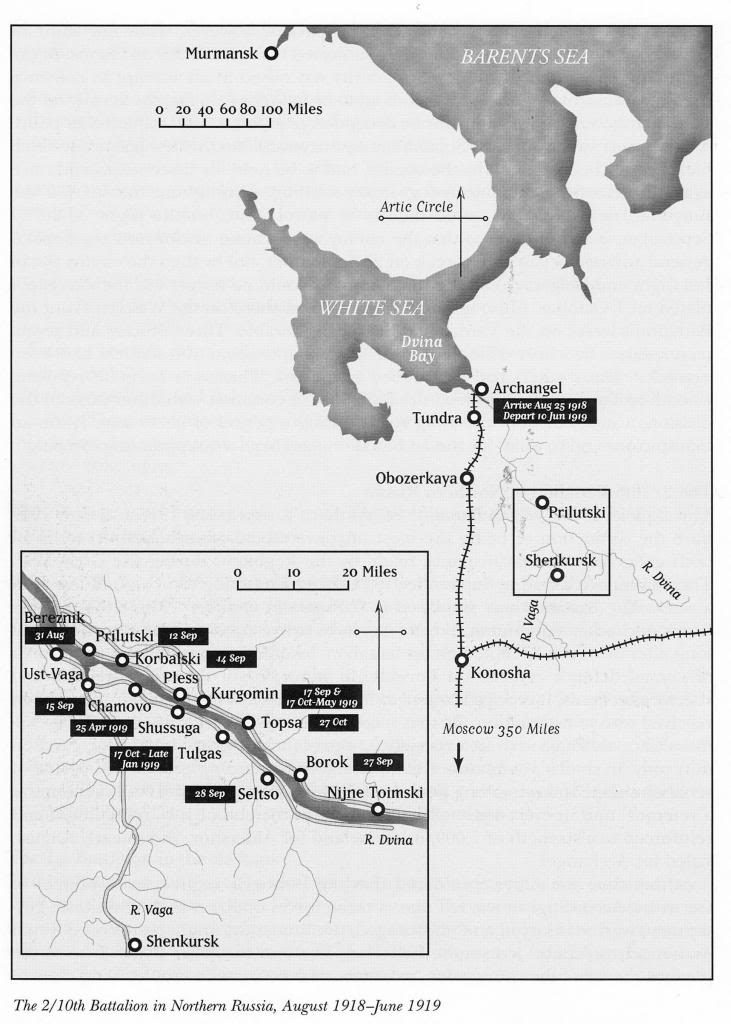

At that time the Allies considered that the Russian Bolshevik regime was a puppet of Germany. Accordingly it was felt that, if those forces opposed to the Bolshevik government were reinforced and encouraged, the Romanovs might be restored. From Archangel two routes led south towards Moscow some 500 miles away: the railway line and the River Dvina. Due to the physical nature of the countryside, movement was restricted to routes lying close to the river line. In the area of operations the Dvina was between one and three miles broad and the surrounding countryside was flat, marshy and densely forested. The enemy consisted of Bolshevik columns that appeared to have little if any local support. On 26 August three companies embarked on barges at Archangel and, five days later, reached the village of Bereznik near the confluence of the Dvina and Vaga. The area of operations was in the lower Dvina and extended some 60 miles south east of Bereznik.

The first action occurred on the night of 11 September when an attack by a Bolshevik column was successfully repulsed. Shortly afterwards a small force continued its advance up the river and captured a 76mm (3-inch) gun and a staff officer who provided useful information. The gun was brought back to Linlithgow by the Battalion and is now located by the Keep in Glencorse Barracks by Penicuik. The advance up the river line continued sporadically for the next two months. Progress was slow, largely due to the terrain, and there were frequent lively engagements. By late October the deteriorating weather forced the troops to retire to more easily defensible positions. In late October there was a severe setback when an attack on the village of Topsa was unsuccessful and the Battalion’s losses were about 80 killed, wounded or missing.

The ‘Archangel’ Gun

Ironically, on 11 November, the day when the war in other theatres was coming to an end, the enemy mounted a major attack supported by gunboats. The attack on the right bank was checked without difficulty but, throughout the day, there was fierce fighting on the left bank during which the outcome was never certain. The resistance was desperate and is perhaps best typified by Sergeant Salmons who rushed into the midst of the enemy firing a Lewis gun from the hip until he was killed. By nightfall the surviving Bolsheviks began to withdraw and the battalion moved back into those buildings from which they had been driven during the day. Several hundred of the enemy had been killed or subsequently died of their wounds, or exposure, while the Battalion’s losses were 19 killed and 34 wounded. The determination of the defenders was acknowledged by the award of three Military Crosses, two Distinguished Service Crosses and three Military Medals.

Private John Stewart left this account of the action on 11 November.

It was on the 11th day of November, in the early hours of the morning, we were suddenly alerted by a terrific bombardment of rifle and machine-gun fire. We were surrounded on all sides. Hastily dashing out with rifle and hand grenades, we threw ourselves on the frozen ground firing as fast as we could. Many by this time were killed or wounded. Our two officers, Lieutenant Hastings and Captain Shafto, standing with pistols in one hand and directing operations with the other, led charmed lives. How they were not killed was a miracle. Then all at once things began to happen. The Canadian artillery appeared on the scene and directed a goodly supply of shrapnel at the advancing Bolshies, killing and wounding many until they retreated back into the forest. But they had not given up the fight. They continued machine-gun fire from the cover of the forest and it was at that point I received my own souvenir, a bullet in the lower part of my chest. It was now getting dark and one of my comrades, noticing me lying on the ground, came forward and cut my field dressing from the inside of my tunic. He was in the act of applying it to my wound when a sniper’s bullet got him in the head and he lay dead beside me. I don’t know how long I lay there. I was gradually freezing to death. I knew I must try to get away. It was now dark and I saw a light in the not too far distance, like a door opening and shutting, so gathering my remaining strength, I staggered towards it and was overjoyed to find it was an American casualty clearing station. What a mess it presented inside, dead and wounded side by side. My own wound was soon attended to, sterilised and bandaged. Given a dixie of hot bully stew and a good tot of rum I soon revived.

By mid-November active operations began to dwindle as the countryside fell into the icy grip of the Russian winter. The Dvina and its surrounding marshes froze and snow fell to a depth of between five and ten feet. Movement through the forests was now relatively easy for those equipped with sledges, snow-shoes or skis. The troops were issued with snow boots, sheepskin coats, fur hats and gloves and, according to their abilities, were reorganised into snow-shoe or skiing platoons. Patrolling remained a regular feature of life, despite the weather. Those in forward positions lived in blockhouses while the remainder were billeted in villages.

2/10RS escort a military funeral in Archangel

In late January 1919 the enemy resumed hostilities and some forward positions were abandoned. As the winter abated the enemy began to mount offensive operations on the Vaga although there was little change in the position on the Dvina. By the spring it was becoming clear that the allied intervention in northern Russia had no prospect of strategic success. In May the American troops were withdrawn but Britain was slower to face up to reality. However, in June the Battalion was relieved by the 2nd Battalion The Hampshire Regiment which allowed it to move to Murmansk. A few days later the Battalion embarked at Murmansk and sailed into Leith on 18 June 1919. They marched through cheering crowds from the Imperial Dock to Leith Central Station en route to Redford Barracks where they were to be demobilised.

The Battalion had been in existence for five years and, although it had only seen operational service for ten months, it had suffered 132 fatalities. It also achieved the distinction of gaining for the Regiment the battle honour ‘Archangel 1918-1919’, the only battle honour won during the war by a second-line battalion of the Regiment and an honour shared with just two other regiments of the British Army.