SHIPWRECK of the Premier in the GULF OF ST LAWRENCE, CANADA, 4 November 1843

and A Useful Cigar

Reminiscence, signed ‘Old Royal’:

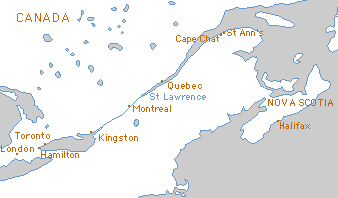

“In 1840, the 2nd Battalion, 1st or Royal Regiment of Foot, left Montreal, for London, (Ontario), going by canal – sometimes towed by small puffers (steamers), which had to leave the boats on passing cateracts. On these occasions we went ashore and pulled the boats past the cateracts with ropes.. In this way we got as far as Hamilton, whence we had six day’s march to London. We had no beds at night, we just picked out the softest place handy and our knapsacks did for pillows. Rations consisted of 1lb biscuit and 3/4lb salt pork, with sixpence a day pay – such were the rations and marching pay in those days in Canada.

We lay in London for about 3 years. Leaving London, and previous to going to the West Indies, we were stationed in Toronto for three months, from whence the right wing proceeded to Quebec to embark for Barbadoes. The left wing and headquarters followed by steamer as far as Kingston, and afterwards in flat bottomed boats to Montreal, passing cataracts and cascades en route, till we came to Lachine rapid, which run at railway speed.

Here an Indian – with an eye like a hawk and an arm like Hercules – took charge of the boats and guided them over the terrible fall of water. We arrived safely in Montreal, embarked on a river steamer for Quebec, where we lay for 5 or 6 weeks. In October, the transport ‘Premier’ arrived, and we embarked for Barbadoes.

After being at sea for about 2 days the captain of the ship lost his reckoning and hugged the shore too close. About 4 o’clock one morning, during a fearful snowstorm, some 300 miles from Quebec, we were driven on a reef of rocks near Cape Chat. The ‘Premier’ lost her rudder and a large hole was knocked in her bows. We were then driven on to a sand bank, the masts had to be cut away and the ship became a total wreck, All the men behaved like true Britons – there was not a murmur – everyone obeying orders as on parade. We could get no help on account of the sea and surf running so high. There were 2 guns on board, but we were unable to fire them, and the blue lights that we carded would not burn as they had got wet, so we had to make use of our small arms to attract the attention of the the shore folk.

The Wreck of the Premier

At daylight, an officer and two men got into a boat in order to try to get a rope ashore, the boat, however, capsized and the rope was lost, the men just managing to escape. At length, we succeeded in getting a rope ashore and by hand over hand work all were safely landed. It took us from 10 am, to 8 pm to get clear of the wreck. I may say that all hands behaved well, – no hurry or confusion – everyone waiting patiently for his turn. We were told off by sections for the boats, and nothing could have excelled the steadiness and obedience of all ranks during the long wait for the boats. The women and children and the colours were the first to be landed, and were taken to St Ann’s, a fishing village about 5 miles off. The tug-of-war came when we were all landed, and there were only a few empty huts for shelter during the night. The fishermen used these huts to store their seed potatoes in. We lit a large fire and then roasted the potatoes, as there was nothing else to eat, officers and men shared alike.

When morning dawned it was indeed a dreary prospect – no breakfast – nothing but a wild forest to look at. A boat was put off to the wreck to try and get what it was possible to save, which was not much. The tea sugar, and flour were completely soaked with salt water and we were able to find only a few things worth taking with us to St Ann’s. The fishermen did all they could for us but they had not food sufficient to last for us and themselves all winter, so word had to be sent to Quebec. There was neither telegraph nor railway and the only way was through a dense forest extending for about 250 miles.

We had a gallant young officer, Lieutenant Dan Lysons, who undertook to go there and inform the authorities of our disaster and troubles. One morning, about three weeks after he had started, we were getting ready for parade, when large government steamer hove in sight. At first we were doubtful whether it was intended for us or not, but to our delight, she fired a gun and sent boats ashore. Hearty chears were raised both on board and in shore. We were soon embarked and the captain treated us like gentlemen, gave us plenty to eat and drink and looked after us well in every respect.

On our arrival at Quebec, all ranks were entertained by the 68th regiment, who had fires and a good substantial meal awaiting us, a delightful change after 3 weeks of salt fish and biscuits at St Anns. That winter we were stationed in the Jesuit Barracks, Quebec. In the spring of 1844, we left for Halifax, and lay at St George’s Island awaiting transport to our destination. We filled three ships ‘Hermes,’ steamer, ‘Pique,‘ frigate, and ‘Eurydice,‘ frigate. After a very Stormy passage across the Gulf of Florida, we at length arrived in Barbados, – spent 3 very pleasant years there and then sailed for home.”

After Note. Amongst those on board the Premier was Pte Joseph Prosser who, in 1855, was to win the Regiment’s first Victoria Cross (VC) for his actions before Sevastopol in the Crimea.

A Useful Cigar

Ensign Waddilove was born in 1825, and was gazetted to the 2nd Battalion which was then in Canada, on July 22nd 1842, at the age of seventeen. He was on board the transport Premier when it was wrecked off Cape Chatte, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, on November 4th, 1843, when carrying the Headquarter Wing of the 2nd Battalion to the West Indies.

Sir Daniel Lyons, G.C.B. (then Lieut. D. Lyons), writing in his ‘Early Reminiscences’, gives an account of the shipwreck, from which the following extract is taken:

“The Captain gave orders for the gun to be fired, but the ship’s powder was damp, so I got my powder-flask from my cabin and placed Ensign Waddilove close to the gun with a lighted cigar in his mouth. After many ineffectual attempts, we at last succeeded in getting the gun to go off, and then continued to fire at intervals, the cigar proving to be an excellent slow match, though Waddilove did not find its flavour improved by its novel application.”