ARRAS APRIL-MAY 1917

The Battle of Arras began on 9 April 1917, preceded by a four day bombardment, and lasted until 16 May. Its aim, as for the Somme in 1916, was to break through the German line, this time in conjunction with a major French assault, the Nivelle Offensive, 50 miles to the south. The French attack was timed to start a week after the British attack allowing the latter to, hopefully, draw German troops away from the French front.

Arras, in contrast to the Somme, was a highly successful offensive (although still hugely costly in casualties), at least in its early stages. Probably the greatest single reason for its success was the effectiveness of the artillery bombardment which destroyed much of the German’s wire and artillery and devastated the defenders. Furthermore the preparations for the offensive were comprehensive and the orders detailed and timely. Unfortunately the weather was foul, with a very heavy snowstorm on the night of 9 April which prevented the artillery deploying forward to support further advances after the gains of the first day; and the failure of the French offensive, which to reduce the pressure on them, meant the British attack had to be continued long after it was capable of achieving proportionate tactical gains.

While Scottish battalions had more than played their part at Loos, in 1915, and on the Somme, in 1916, Arras saw the greatest concentration of Scottish battalions in any of the set-piece battles of the war. With the 9th and 15th (Scottish) Divisions and the 51st (Highland) Division, together with a number of Scottish battalions in other Divisions involved, there were a total of 44 Scottish battalions committed to the battle including eight from The Royal Scots, the 2nd, 8th, 9th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 15th and 16th. One-third of the 159,000 casualties were Scottish. As well as the Scottish battalions there were seven Canadian battalions with Scottish heritage, including The Canadian Scottish, and The Newfoundland Regiment (the Royal Newfoundland Regiment from 28 September 1917 – the only Regiment to be so honoured during the 1st World War), both of whom were later allied to The Royal Scots.

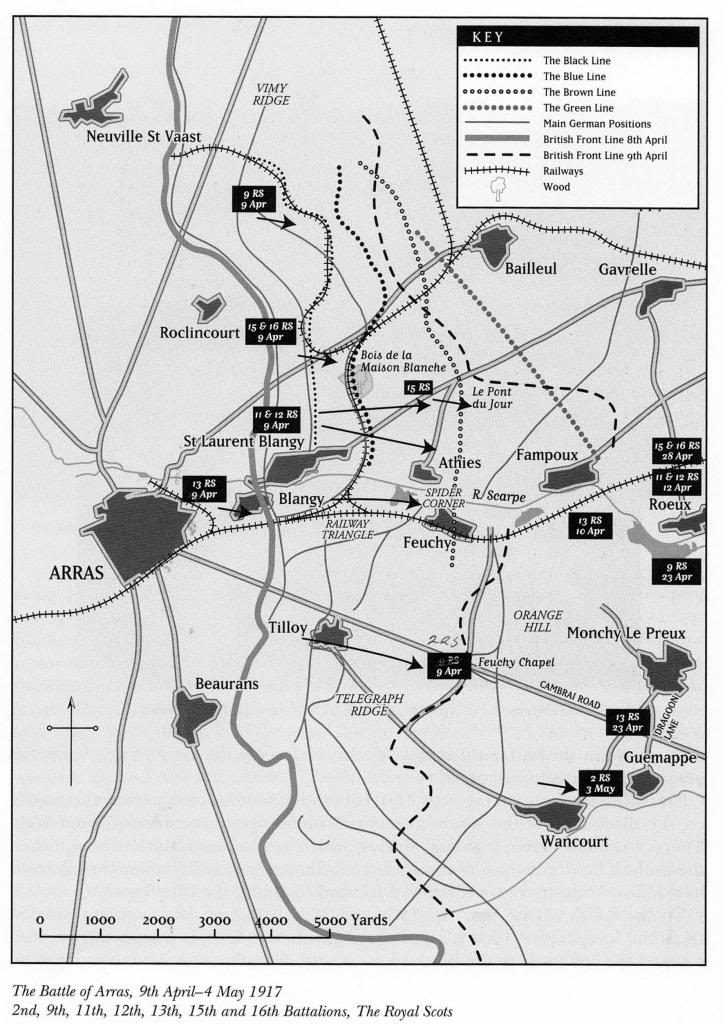

The initial attack was carried out in phases in which colours were used to indicate the successive lines of objectives for the assaulting troops (see map). The 9th Battalion, serving, together with the 8th, in 51 (Highland) Division, took part in the assault on the Black Line at the southern end of Vimy Ridge (which was taken by the Canadians) in the area of Poser Weg. The Division was relieved on 12 April, by which time the 9th had sustained some 240 casualties. After three days rest, the Division re-entered the battle, in the Fampoux area, on 15 April.

Infantry leaving the trenches 9 April

The 15th and 16th Battalions were serving with 34 Division south of Roclincourt. Initially the 16th led the assault with the 15th in support. The fighting was intense and much raw courage was called for from both battalions. By the time the 15th was due to advance on the Brown Line its fighting strength had been reduced to only four officers and not much more than 100 soldiers. Both battalions were relieved on the night of 14/15 April until returning to the line, in the Point du Jour area, on 23 April.

The 11th and 12th Battalions, serving in 9 (Scottish) Division were next to the South. The war diary of the 12th describes the advance to the Brown Line as ‘effected like a drill parade, correct dressing and distances being kept between ‘waves’ being maintained throughout’. Although casualties were high, some 300, mostly wounded, between the two battalions, but including the Commanding Officer and, later, the RSM of the 12th who were both killed, the Division had secured all its objectives by mid-afternoon and the leading units of 4 Division passed through to secure the Green Line.

South of the River Scarpe, the 13th Battalion was serving with 15 (Scottish) Division. Its initial objective was to secure the village of Blagny. At first some fierce opposition was encountered but the combined use of Stokes trench mortars, rifle grenades, recently introduced and, according to the War diary, much more effective (and safer for the user) than the hand thrown version, and sheer human aggression enabled it to capture the village by 9am. Pte Clark, from West Croydon, in London, and a ‘collector’ in civilian life, who had joined the Battalion in August 1916, left this description of the events of 9 to 12 April:

‘The battalion moved up to the front line at midnight, for the attack was coming off at 5.30 am 9th. I am on duty 5.0 am bombardment terrible all previous day and night, 5.25 am all officers getting excited, bombardment gradually ceases, and all quiet at 5.28. Its raining a little but the sun is trying to shine, 2 mins peace. And then, at 5.30, the most wonderful and perfect besides terrible bombardment of the War. The earth shook all over, and at the same time the lads are over the top, the bombardment keeps up, and the range is lengthening as they go on, the CO is waiting anxiously for news, we are watching the boys from our point of vantage, everything going well, a runner from one of the captains arrives, battalion going strong and artillery splendid, very few casualties, but hundreds of prisoners, have taken Blagney, first objective and still pushing on, artillery also advances, and big guns keep up bombardment, everything goes well, at night we shift up to a new position deep German dug-outs at Railway Triangle, we stay there the night, and then move up further along the railway, we stop on the embankment lyeing (sic) in support, have advanced 5 miles, Germans reached new position and holding another division up, we lay in shell holes for three hours, heavy snowstorm on, very cold, and Germans bombarding railway heavily. Stayed here all night and early morning of the 11th was called out to reinforce 37th Division. Battalion suffered pretty heavily by snipers and machine gun fire, but was successful in taking along with the rest of the brigade, the 37th Division’s objective. it was a hell of a time, you couldn’t move for snipers, we were in this state all day, but were relieved in the early morning of the 12th and came back to our old positions of the 9th, but was unrecognisable having had an heavy bombardment. During the day we moved into Arras again and I tell you we were glad to get a rest, and had nothing but a few biscuits during the last 4 days, and the drop of tea we got in Arras, was the best I’ve tasted in my life. In all we advanced 9 kilometres, a little over 5 mile, taking thousands of prisoners, plenty of guns, large and small, and tons of ammunition and material.’

12 RS Lewis gun team wearing respirators

To the south of the 13th Battalion the 2nd was serving in 3 Division. It was not involved in the initial assaults but it took over the lead from just east of Tilloy and advanced nearly three miles towards Feuchy Capel before being halted by enemy resistance.

The attacks of 9 April had been a huge success but, sadly, exploiting the initial gains was rendered all but impossible by the weather. The intermittent rain that had fallen during the day developed into a driving blizzard of snow and sleet throughout the night. Such conditions could be miserably endured by the infantrymen in forward positions, but it made it impossible to move guns and limbers forward to better support the advancing troops. The initial success was, however, marred by the need to resume offensive operations on 23 April to provide some relief for the disastrous French attack further south. Both the 9th and 13th Battalions were involved in the initial resumption of operations and both suffered severely. The 9th lost some 60 killed, 115 wounded and 55 missing (probably killed) in inconclusive fighting near Roeux and, consequently, it had to be relieved. The 13th experienced a similar reverse to the south of Monchy. Its attack, despite repeated efforts to move forward, was halted by the enemy in the area of Dragoon lane with the loss of some 30 killed, 170 wounded and over 70 missing. Again Pte Clark’s diary tells us of his experiences.

‘On the night of the 21st we went into the line again, Saturday night, and we went over the top again on the 23rd, we were shelled pretty heavy during the two days, Coy Headquarters being in a cellar on the left of the Cambrai Road. The 23rd arrived, my Coy was brought back out of the front at 2.30 am to a trench 70 yards back, I don’t know why but it proved disastrous, at 4.30 am we kicked off, but got a terrible bombardment from the Germans. I hadn’t gone far when I was buried by a shell, I don’t know how long I was there, but when I got going again, the Coy was not to be seen. I went on again and found my pal Mac, he had also been buried, and was wandering about like a lost sheep, we both went on to find the battalion, but strayed and got mixed up with the Worcester Regt, they were supposed to be on our left, but were all mixed up, we decided to stop with them, and assisted the stretcher bearers. I dressed a wounded officer and he gave me a 20 Franc note out of his pocket book as a souvenir, it was all torn shrapnel having hit his note book, and going right through, we stayed with this regiment till Tuesday (the 24th) when somebody told us the Scots had been relieved, so we went also, we got back into Arras, and reported but found the battalion had not been relieved yet, they told us to rest and get some grub and next day we were to go back again. I had run out of fags, so had to bust the wounded officer’s souvenir. We left to join the battalion again Wednesday afternoon and found them at night, the Signalling officer told us to stop at headquarters, our pals were glad to see us, as we were reported missing, we shifted up to new headquarters at night, in some old German gun-pits, it was cushy here, but fierce fighting was going on up the front line and the battalion had suffered heavily. Friday night (the 28th) I was put at an advanced headquarters up the line, it’s a good job we wasn’t shelled much, we only had a waterproof sheet covering us, the wire also kept pretty good, only breaking twice, we stayed here all day Saturday, and we nearly fainted with joy when we heard we were being relieved that night, it was early Sunday morning when we left, what was left of us in my company (D Company), there were no officers left. Only 1 Lance Corporal and 17 men, if I hadn’t been buried I don’t suppose I should be here now, it was the worst time of my life, and how I got through it all I don’t know. We arrived in Arras about 5.30 am Sunday morning, had a good tot of rum which nearly knocked us all drunk, cigarettes, chocolate, and cake were supplied by the Padre, and the remaining officers, they also sprang it on us again at breakfast, 2 fried eggs and ham for breakfast.’

The original of Pte (later L/Cpl) Arthur G Clark’s unpublished diary, Diary pour la Guerre, is in the possession of the Imperial War Museum. He took part in the Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) in July and August 1917 and suffered the discomforts of trench life during the winter of 1917-18. He was killed in action near Bethune on 27 August 1918 and is buried in Hersin Cemetery.

The lack of Officers and NCO’s amongst the survivors of D Company may well have resulted from an apparent (very sensible) German policy of targeting commanders leading an assault, as shown by a comment from Major Mitchell, by then acting Commanding Officer of the 13th Battalion, in the War Diary. ‘ … I would also suggest there was a considerable amount of close range sniping. I have arrived at this conclusion from the number of Officers and NCOs I had killed here. All my Company Officers and all my Sergeants and most of my Corporals, became casualties early in the operations. This accounted for the fact that no information was received for (? Note: this may be a mistype for ‘from’) Companies and it prevented the necessary organization being carried out. The men were prepared to hold the ground they had gained but they were incapable of re-organizing for a further advance.’

On 28th April the 15th and 16th Battalions, both now only 400 strong, were in action in the area of Roeux. Sadly they were no more successful than the 9th had been earlier. The 15th suffered nearly 300 casualties and the 16th over 300.

The experiences of the various battalions of the Regiment at the end of April were typical of all units in the Arras area. Nevertheless, because of the continuing need to assist the French, the offensive was resumed again on 3 May, involving the 2nd and 12th Battalions in further fighting. The 2nd ’s attempt to advance in the area of Monchy le Preux on 3 May was a disaster. The day was spent pinned down by fire in front of the enemy’s wire and having to endure the full force of the sun. When night fell those survivors that were still capable of movement made their way back to their original positions. The following night they were relieved having lost 12 officers and 254 soldiers since 24 April. South-east of Gavrelle, on the night of 3/4 May, about 150 members of the 12th Battalion, by now virtually the combined strength of two companies compared to the establishment of 227 for one, attacked the German lines in front of them to assist the escape of three companies of 6th Battalion The King’s Own Scottish Borderers who had been cut-off in an attack earlier that day. Many of the Borderers made it back, but at a cost of over 120 casualties to the 12th Battalion.

The 8th Battalion had worked ceaselessly at its pioneer tasks in support of 51 (Highland) Division throughout the battle of Arras. The dangers of working close to the front line were clearly demonstrated by its casualties of ten officers and 93 soldiers killed or wounded in April and May. When these are added to the losses of the other seven Royal Scots Battalions involved at Arras, the total figure amounts to over 3,100 casualties in less than four weeks.

Such gains as were achieved on 3 May were wholly out of proportion to the heavy losses sustained and, soon after this, all fighting on a big scale in front of Arras came to an end for the year. The pressure was still on the French, however, and the need to relieve this simply moved the action north to Flanders and the Third Battle of Ypres, or Passchendaele as it is more often known, which opened on 31 July.

Passchendale