THE LISBON MARU

Background

The Lisbon Maru sailed from Hong Kong on 27 September 1942 en route to Shanghai and Japan. She was armed and carried, in addition to 1816 British POWs, 778 Japanese troops and a guard of 25 for the POWs. There was nothing that identified her as carrying POWs.

The British POWs were mostly drawn from The Royal Navy (379) ‘accommodated’ in No 1 Hold at the front of the ship, 2RS (373) and 1MX (366), with others from various cap badges to a total of 1077, ‘accommodated’ in No 2 Hold forward of the Bridge and the RA (380) ‘accommodated’ in No 3 Hold at the stern. The Senior British Officer on board was Lt Col HWM Stewart, CO 1MX, in No 2 hold. Conditions in all three holds were very crowded.

Just after 0700hrs on 1 October, in a position 6 miles off the Sing Pang Islands in the Chusan (now Zhousan) Archipelago off the coast of Chekiang Province (south of Shanghai), the Lisbon Maru was hit in the engine room, at the stern, by a torpedo fired from the US submarine USS Grouper. The engines stopped, the lights went out and those few POWs who were on deck were pushed back into the holds. The ship’s gun began firing. The POWs were kept in the partially closed holds throughout the day with no food, water or access to latrines. No blame has ever been, nor ever must be, attached to the USS Grouper. There was nothing that identified her as carrying POWs; there were a large number of Japanese troops on board; and she was armed. Everything that could be seen identified the Lisbon Maru as a legitimate target.

At 1700 hrs the 778 Japanese troops were taken off onto a Japanese destroyer and merchant ship which had arrived, leaving the British POWs, their guard of 25 and the 77 crew on board. In doing so they removed the ship’s four lifeboats and most, if not all, of the six life rafts ensuring that none would be available for any possible subsequent evacuation of the POWs. At about 2100 hrs, allegedly fearing the POWs could break out and overpower the guard, the Guard Commander ordered the ship’s Captain to fully close the hatches and batten them down with canvas. Conditions in all three holds deteriorated rapidly. In No 1 Hold two diphtheria patients died and in No 3 hold, nearest where the torpedo had struck, water was rising rapidly. The POWs manned the pumps; but because of the extreme heat and shortage of air some of them collapsed into the water and drowned.

By dawn on 2 October it was apparent that the ship was in imminent danger of sinking and soon afterwards the crew and all but five of the guards were taken off. At about 0900 hrs the ship gave a violent lurch and it was apparent that she could not last much longer. Lt Col Stewart ordered a Royal Scots officer, Lt Howell, to attempt to break out through the battened hatches. He succeeded in doing so and, after being shot at by the remaining Japanese guards, which led to two men being killed, reported to Col Stewart that the situation was desperate and that the ship was in imminent danger of sinking, but that he had seen an island some distance off. Col Stewart gave the order to leave the holds and a number of the POWs rushed on deck, plunged overboard and began swimming towards the island. The remaining guards began firing at them until the weight of numbers of POWs pouring onto the deck overpowered them and, probably, threw them overboard.

Most of the PoW’s scrambled to safety but hundreds of others saw their escape thwarted

By good fortune the stern at this point became stuck on a sandbank leaving the forepart as far as the bridge sticking out of the water for about a further hour which gave sufficient time for all live men to climb or be assisted out of the holds. Many men did not have lifebelts and many could not swim. Between the ship and the islands were a number of Japanese auxiliary vessels and tugs, some of them surrounded by men in the water vainly asking to be picked up and, if they were, then pushed them back into the water; and the firing of shots could be heard. The Lisbon Maru finally sank at about 1045. At some stage the Japanese boats started to pick up those prisoners still alive in the water and who had not drifted past them towards the Islands.

Lt Howell, having been picked up by fishermen in a sampan, was among the first to reach the largest of the Islands and was able to explain to the villagers there that the heads bobbing about in the water were British prisoners and not Japanese. As a result the Chinese set off in junks and sampans to assist the survivors. They picked up a considerable number of exhausted swimmers while other villagers assisted those who had drifted or swum to the islands and helped them to land on the rocky shores. Some 200 survivors were assembled on the islands, where the villagers fed and clothed them from their own scanty supplies and treated them with great kindness until the Japanese landed in force on the following days and rounded up all but three of the prisoners. These three, all civilians who had been working in Hong Kong – two with the Royal Navy, were hidden by the village representative, who later arranged for their escape to Chungking.

Those picked up by the Japanese ships were collected together on the deck of a large gun boat where, exposed to the elements, some died of exposure and exhaustion before finally being landed south of Shanghai on 5 October.

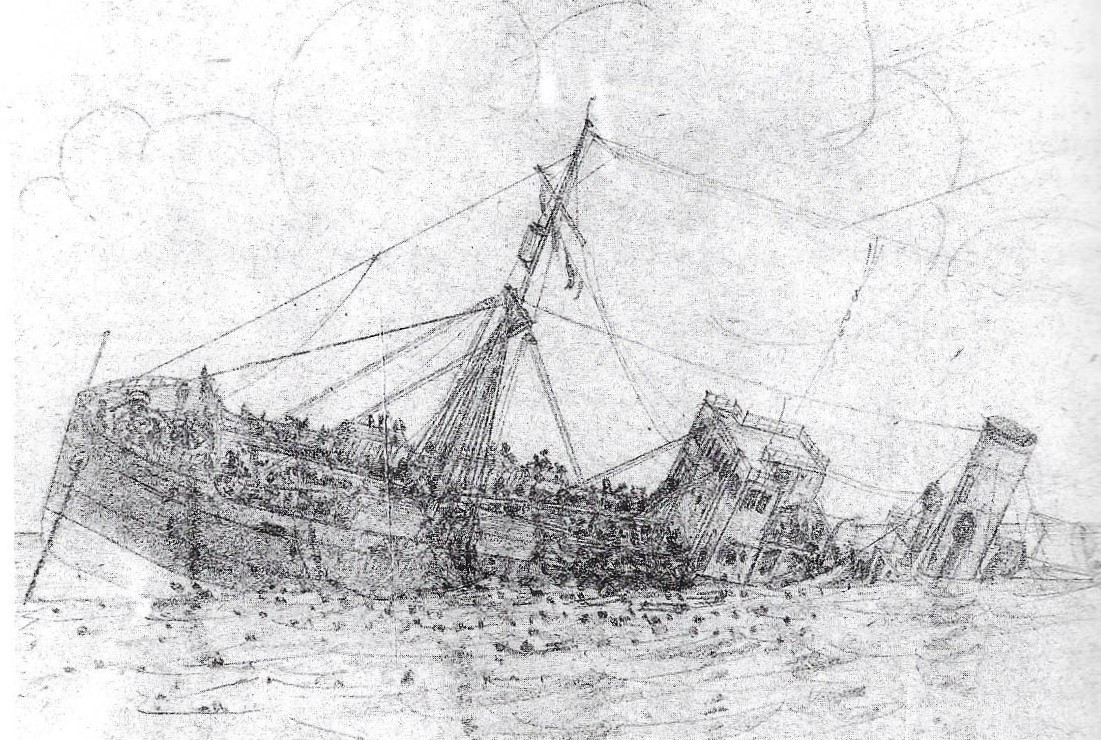

Sinking of the Lisbon Maru in the China Sea, 20 October 1942. A pencil sketch drawn by Lieutenant W C Johnson, US Navy while a prisoner of war at Kobe, Japan and later presented to the Regiment

Of the 1816 POWs who had left Hong Kong only 973 (including the three escapees) survived leaving 843 (46%) who were assumed to have been killed by the Japanese firing on them or drowned – many of the latter being non-swimmers, without life-jackets or other means of support, and some, it was reported, as the result of shark attack. Amongst The Royal Scots a total of 183 died, many more than the 107 killed in the whole of the battle for Hong Kong. Relatively few of the POWs, only those who had died on board before she sank, would have gone down within the ship. The remains of the others will have been scattered in the surrounding seas.

Aftermath

Subsequently Lt Howell was awarded the MBE for his gallantry in breaking open the hold and Lt Norman Brownlow the same award for organising the evacuation of the ship and then, having reached the island himself, obtaining a small boat and rescuing men from the sea who were trying to reach and clamber ashore on the islands.

After the war a fund was organised amongst survivors in order that the proceeds might be sent to to the Sing Pang islanders as a token of gratitude. In February 1949 the Governor of Hong Kong presented to Mr WooTung-ling, the village representative who had hidden the three escapees, and other islanders a motor fishing launch and some monetary awards.

All those who died as a result of the sinking are commemorated on panels at the entrance to the Sai Wan CWGC cemetery on Hong Kong island.

On the 3rd of October 2021 The Royal Scots attended at the National Memorial Arboretum for the unveiling of the memorial to the men who perished on this dreadful day in our history.