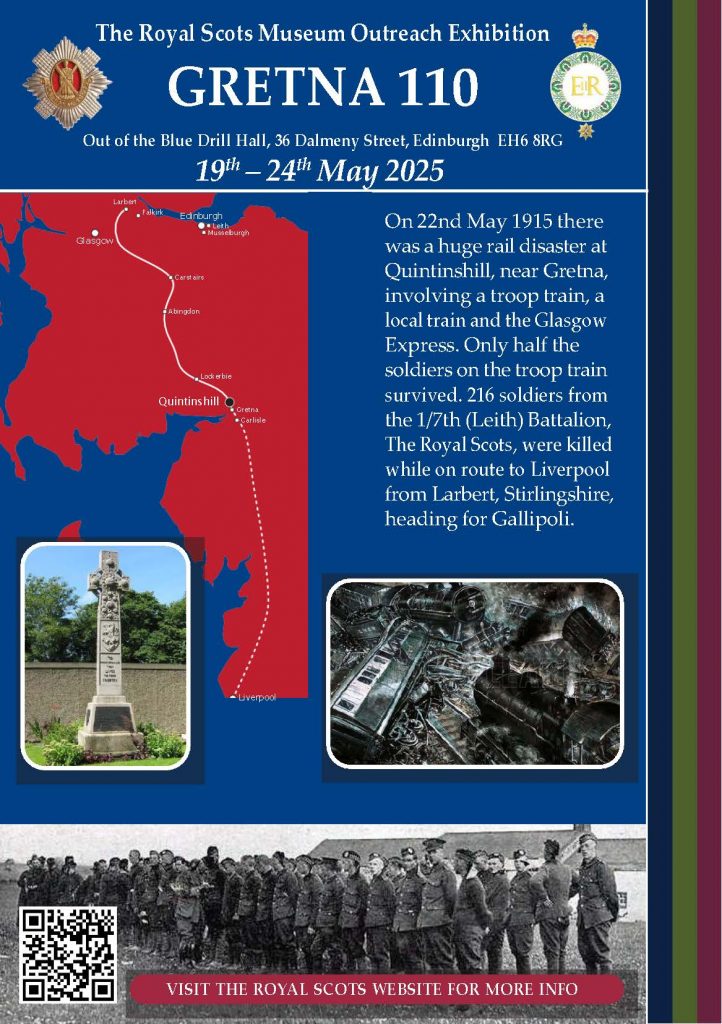

Experience the well-researched exhibition in the former 7th (Leith) Battalion drill hall in Dalmeny Street, just off Leith Walk, during the period 19 – 24 May 2025 to mark the 110th anniversary of the Quintinshill Rail Disaster on 22 May 1915 in which 216 members of the Battalion were killed and many more injured. The Battalion was travelling from Larbert, where it had been training, to Liverpool Docks to board a ship bound for Gallipoli. A local community Remembrance Service will be held at Quintinshill and Gretna on Thu 22 May and the annual Regimental Memorial Service will be held on Sat 24 May in Rosebank Cemetery, where many of the victims were buried.

Details of the train crash, the worst ever in UK, are at http://www.theroyalscots.co.uk: Heritage (1st World War). Further details will follow in the Upcoming Events.

THE ROYAL SCOTS MUSEUM OUTREACH EXHIBITION

This year’s exhibition will commemorate 7 RS and the Gretna Rail disaster, culminating in our annual Service of Remembrance at Rosebank on the morning of 24 May.

The Gretna 110 exhibition will be held at the Out Of The Blue community hub in the former 7 RS Drill Hall in Dalmeny Street 19 – 24, May.

The Out of the Blue Drill Hall was chosen for the GRETNA 110 exhibition as the Drill Hall, located in the close- knit Leith community was the 7th Battalion’s Drill Hall; the majority of the battalion’s men were local to Leith and Musselburgh, with a significant number from West Lothian.

The purpose of the Museum’s GRETNA 110 is to reach out to all generations of the wider community across Scotland to heighten awareness of the worst rail crash ever in Great Britain when 216 Royal Scots of the 7th Battalion were killed on the morning of 22nd May 1915 at Quintinshill, near Gretna, while travelling to fight in Gallipoli. Many more were injured.

Visitors to the well- researched exhibition, focussed on local soldiers and families’ stories supported by a large selection of objects and artefacts, photographs, documents and newspaper cuttings, will be able to experience the detail of the Rail Disaster, its immediate aftermath and learn how survivors went on to fight in Gallipoli and other areas for the remainder of the Great War.

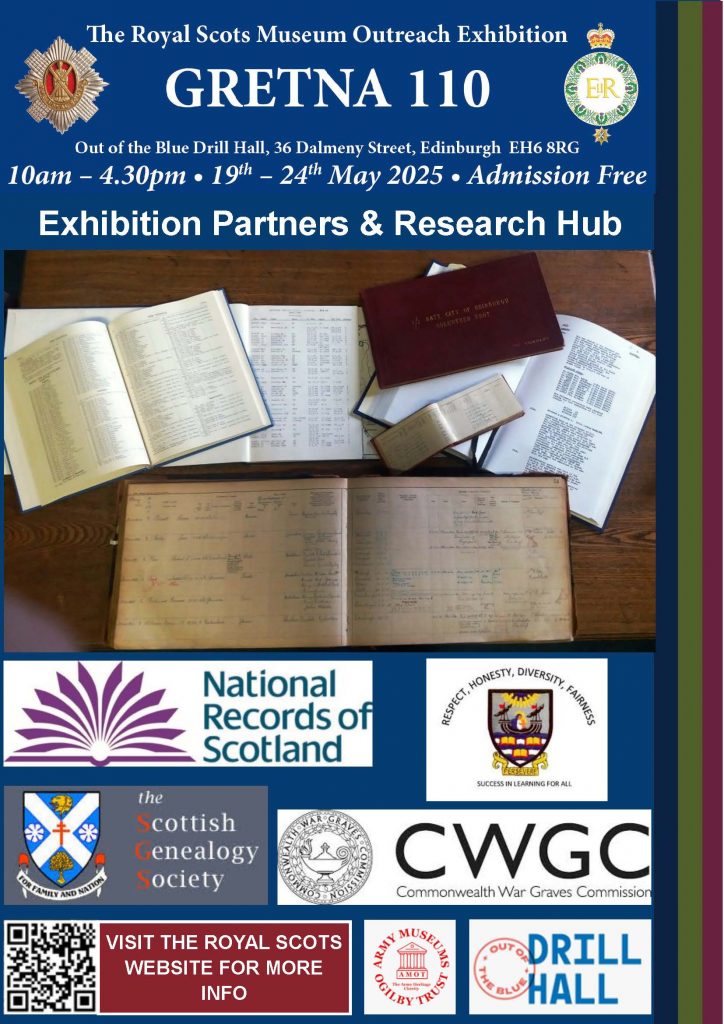

A dedicated Research Room with access to The Royal Scots military records, expert advice on medals, National Records Scotland, the Scottish Genealogical Society and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission is an integral part of the exhibition; this will allow enquiries to be made and advice given on further research sources. Visitors are encouraged to bring their ancestors military documents and medals along.

#SaveTheDate

#Gretna110 #MilitaryMuseumMonday #WhoDoYouThinkYouAre

@LeithAcademy @CWGC @NRScotland @ScottishGenealogySociety @OOTB

GRETNA 110: A Family Story

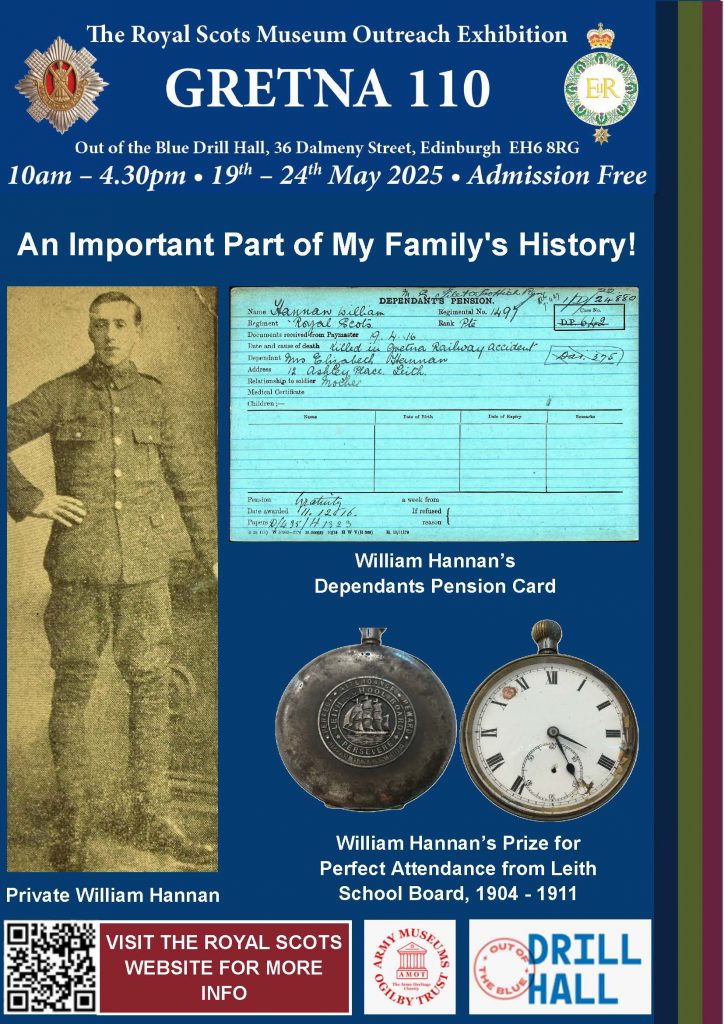

Reflections on William Hannan, killed in the Gretna Rail Disaster.

My name is Ruth; I was born and brought up in Leith, and despite now living in Stirlingshire with my family, I consider myself to be a local descendant of one of the young lads killed in the Quintinshill Disaster.

William my great uncle, the second son of John and Elizabeth Hannan’s eight children, was born in June 1897 at 10 North Junction Street, Leith. The family moving to 10 Ashley Place, close to the Rosebank Cemetery before the outbreak of the Great War.

It is so hard to imagine the shock and horror that the family must have suffered when their son who had gone off to war and had been killed so quickly, before he had even left Scotland.

My own grandfather, Adam, would have just turned 16, yet he too was preparing to join The Royal Scots; just imagine how it must have felt with another son heading to war.

The Out of The Blue 2015 dramatisation of the local families’ experiences including waiting outside the Battalion’s Drill Hall in Dalmeny Street for news, then the identification of bodies and the funeral procession to Rosebank cemetery 100 years before, in the same Drill Hall had a profound effect on me. It helped me to understand part of the reason why the whole generation of our grandparents didn’t “talk war”, and why William’s story was not told down the generations.

I myself would have known nothing further of William, other than inheriting his Leith Academy perfect attendance award watch, had I and my husband, who served in The Royal Scots in the 1970s, not watched a BBC documentary film. The film narrated by Neil Oliver, was shown in May 2015. The cameras rolled over the Rosebank memorial plaques and we spotted a Hannan; we paused the programme, ran to fetch the watch, quickly Googled William Hannan, Quntinshill and there on our laptop was information about my Great Uncle!

There I was, sitting holding his pocket watch, and 100 years to the day since he died, all of his story unravelled, and he became a hugely important part of my family’s history!

For that reason and for the ongoing history of Leith and the loss of so many men “from the streets” it is crucial that the Quintinshill Rail Disaster remains firmly in the history of The Royal Scots, Leith and across Scotland.

#Gretna110 #RoyalScots #MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110Family

GRETNA 110: Event Highlight

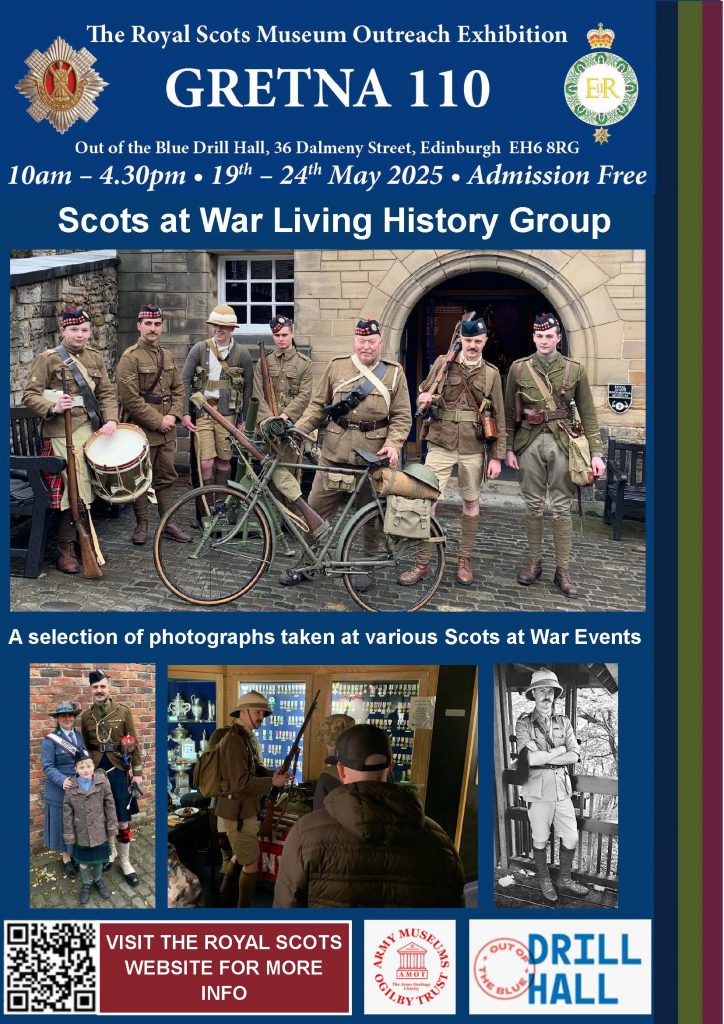

In the upcoming event, GRETNA 110, we will be joined by the Scots at War Living History Group.

The Scots at War Living History Group are dedicated to the memory, study, and appreciation of not only the military, but also the political, economic and social forces that shaped Scotland. Following the lives of soldiers, nurses, factory workers, shipbuilders and more from 1899 to 1945.

#Gretna110 #RoyalScots #MilitaryMuseumMonday @ScotsatWarLivingHistoryGroup

GRETNA 110: Display Highlight

In the upcoming exhibition, GRETNA 110, the displays will take you on a visual journey with the 7th Battalion through their fateful journey to Gretna and beyond. Through the objects left behind, we explore tales of tragedy, loss but also bravery in the face of adversity.

After exploring the events of the 22nd May 1915, the exhibition will highlight the Gallipoli campaign – the original destination of the 7th Battalion. After surviving the wreckage, many of those from the train continued their journey to the peninsula.

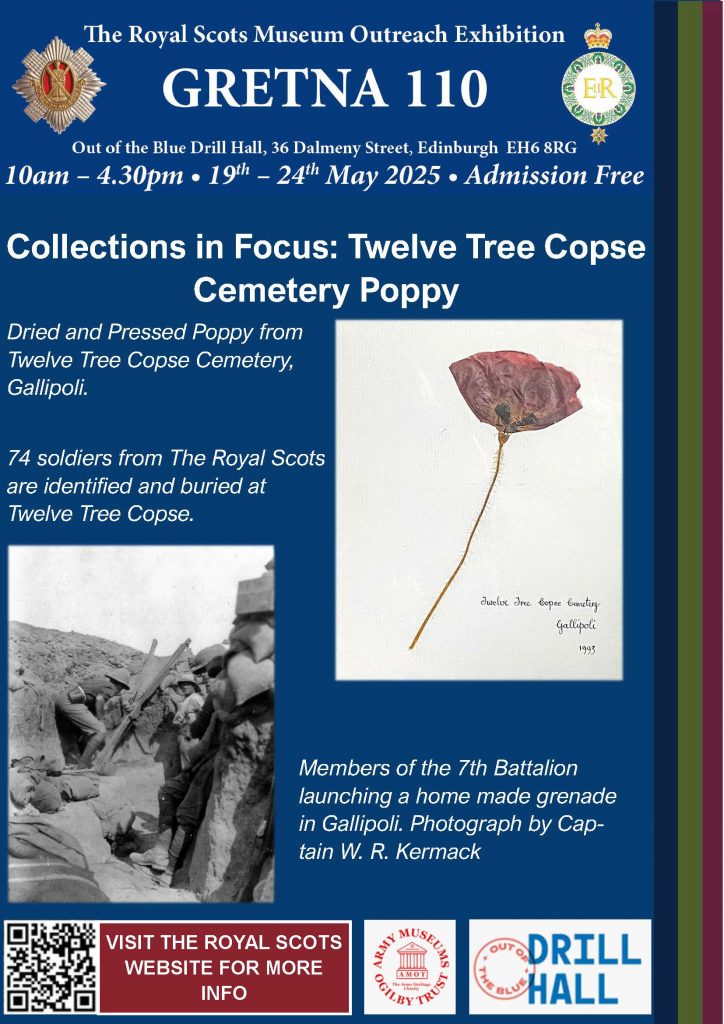

On display will be a framed pressed poppy from the Twelve Tree Copse Cemetery. It is one of over 30 Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries in the Gallipoli Peninsula, and 3,360 First World War servicemen are buried or commemorated there. Of the 1,141 soldiers identified there, 74 are members of The Royal Scots.

#Gretna110 #RoyalScots #MilitaryMuseumMonday

GRETNA 110: Display Highlight

In the upcoming exhibition, GRETNA 110, the displays will take you on a visual journey with the 7th Battalion through their fateful journey to Gretna and beyond. Through the objects left behind, we explore tales of tragedy, loss but also bravery in the face of adversity.

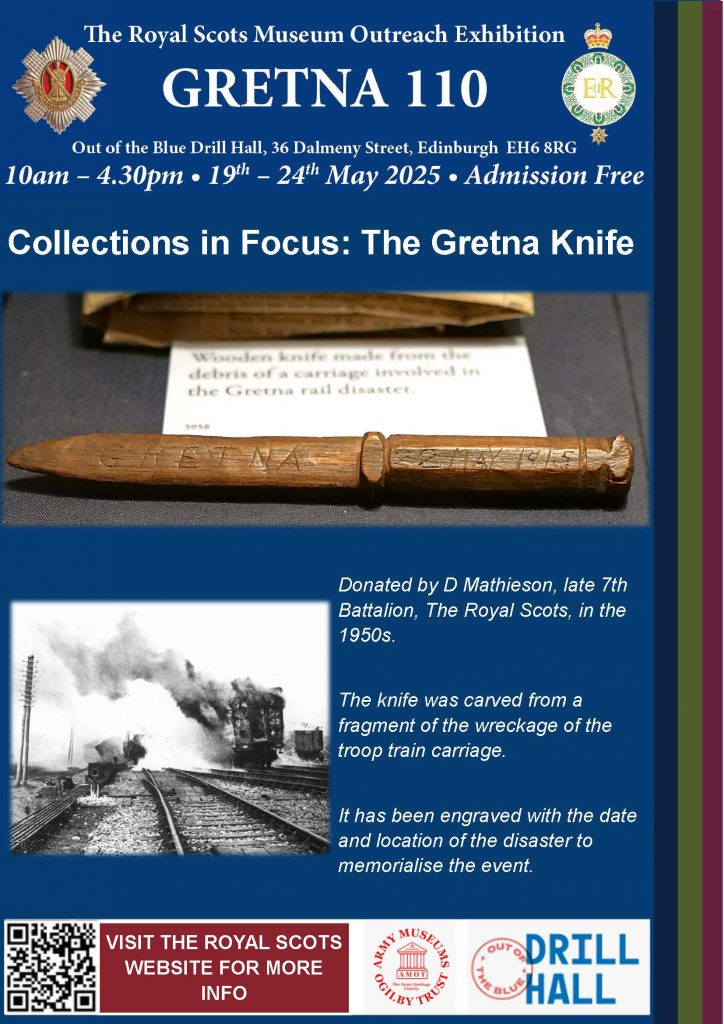

On display will be a small collection of items which survived the terrible fire against all odds. One of the smallest and most unassuming is the Gretna Knife – a wooden knife carved from a fragment of the carriages involved in the crash.

The knife, inscribed with the date and location of the rail disaster, was donated by D Mathieson, a member of the 7th Battalion, The Royal Scots, who survived the incident.

#Gretna110 #RoyalScots #MilitaryMuseumMonday

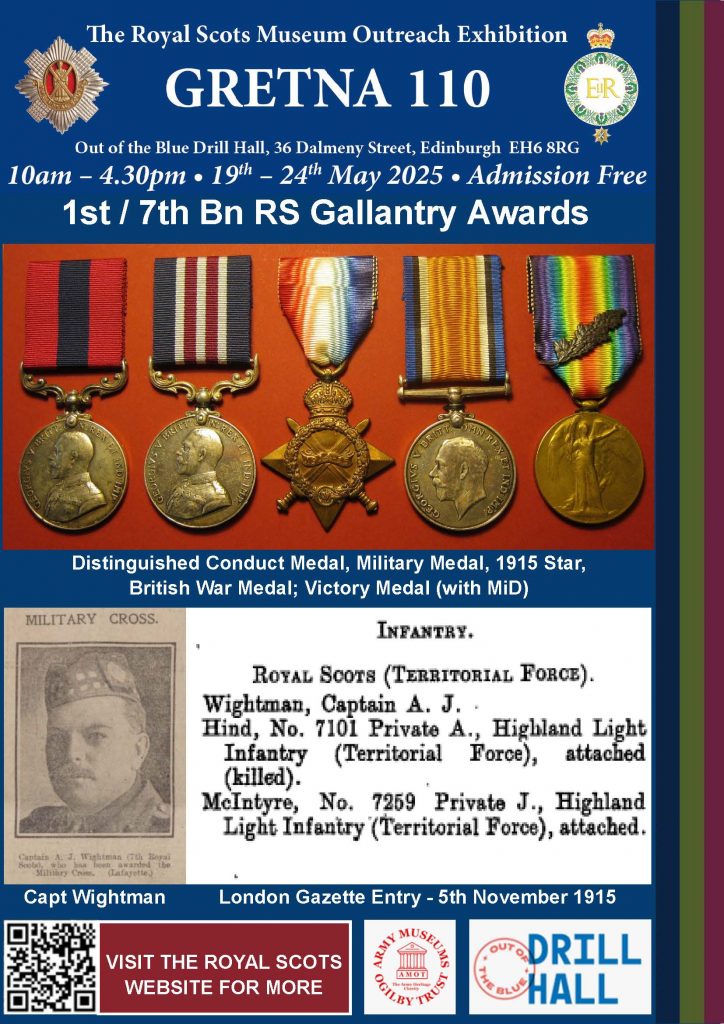

1st/7th Battalion The Royal Scots Gallantry Awards

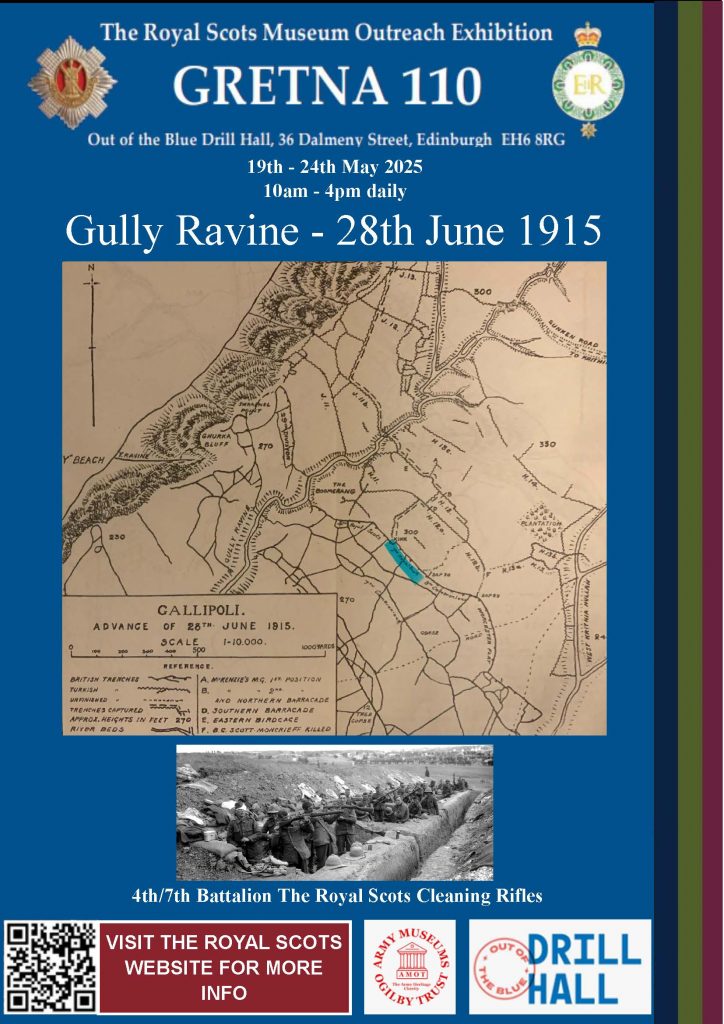

Gully Ravine – 28 Jun 1915

Mention in Dispatches

Privates A. Hynd and J. McIntyre* (both H.L.I. attached 7 RS) did magnificent work in carrying ammunition forward across the fire-swept zone, the former being killed.

Both were mentioned in despatches

When the position had been taken Capt. A. J. Wightman (7 RS) endeavoured to run out a telephone wire, and with Sergeant Rosie (7 RS) he led four signallers carrying cables and instruments towards the captured trench. In the course of this brave attempt Sergeant Rosie was killed and Capt. Wightman wounded, though the latter carried on till every man was knocked out and he himself was again wounded and fell. He lay out all day, was hit a third time, but recovered sufficiently to crawl into our lines towards dawn next morning.

Capt Wightman was mentioned in despatches and was subsequently awarded the Military Cross for this action. This was the only M.C. awarded to the 156th Brigade immediately after this action, largely because there were few officers left to make any recommendations.

When the 7th Battalion The Royal Scots had lost all their signal section at Gretna, Captain Wightman had stepped into the breach and trained his men on the voyage out.

* McIntyre was also awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal later for his action in July 1915, and his mention in despatches was later upgraded to a Military Medal when this was established in 1916.

#Gretna110 #RoyalScots #HLI #Gallantry #MilitaryMuseumMonday

The Battle of Gully Ravine 28 June 1915

156th Brigade

Orders For Attack, 28 June 1915

The 156th Brigade has been detailed to attack trenches H12 a; H12; H11, and the ravine Northeast of H11, as far as the communication trench at the head of the ravine.

The assaulting party will consist of:-

8th Battalion The Scottish Rifles less 2 Coys

7th Battalion The Royal Scots less 1 Coy

4th Battalion The Royal Scots less 2 Coys

Each man of the assaulting party will carry 200 rounds of ammunition, 1 equilateral piece of tin tied with string loops around the shoulders, 2 sandbags tucked into the belt, entrenching implement, iron ration, full water bottle, no pack or entrenching tools will be carried.

7th Batatlion The Royal Scots War Diary

The 7th Battalion The Royal Scots were only two companies strong, one of their own men, and one of HLI attached.

The bombardment started at 0900, reported through brigade headquarters that shells were bursting a little short a few minor casualties resulting.

The 7th Battalion The Royal Scots were led by Major A W Sanderson and their own company, the second and third lines being formed from the company attached from the 8th Highland Light Infantry.

Promptly at 1100 Capt Dawson, commanding C Company, gave the order to attack, without hesitation or wavering the men sprang over the parapet and dashed forward. They appeared to have very few casualties when the first trench was reached H12a. The Turks cleared off to our right and offered little resistance. The right, Machine Gun & Shrapnel Fire was terrific, with practically no delay they continued against H12. During this advance most of the casualties occurred.

The support and reserves left following at 75yds from the line in front and by the time H12 was reached both lines were practically consolidated. The Turks again after little resistance retired by both flanks and by Trench P. This unit was in touch with the 4th Battalion The Royal Scots on left flank but on right touch was not well maintained with the 8th Scottish Rifles.

Application was made at 1500 for reinforcements to come up on the right to occupy empty trenches. One platoon Scottish Rifles came up but not being sufficient the right was rather in the air.

H12X was a poor Turkish trench H12Y very good. It took the remainder of the day to convert H12X into a suitable fire trench and to block Trench P.

The Hampshire Regiment started to relieve the 7th Battalion The Royal Scots at 2130 which was completed at 0030.

The 7th Battalion The Royal Scots had left Larbert on the 22nd May at full strength, 31 officers, including attached, and 997 other ranks. The Gretna Disaster, coupled with little more than a fortnight on Gallipoli, had reduced it to 7 officers and 217 other ranks.

On the 6 July 1915 the remaining two companies of the 4th Battalion The Royal Scots and remaining company of the 7th Battalion The Royal Scots were formed into a composite battalion under the command of Lt Col W. C. Peebles.

#Gretna 110 #MilitaryMuseumMonday #GullyRavine #RoyalScots #HLI

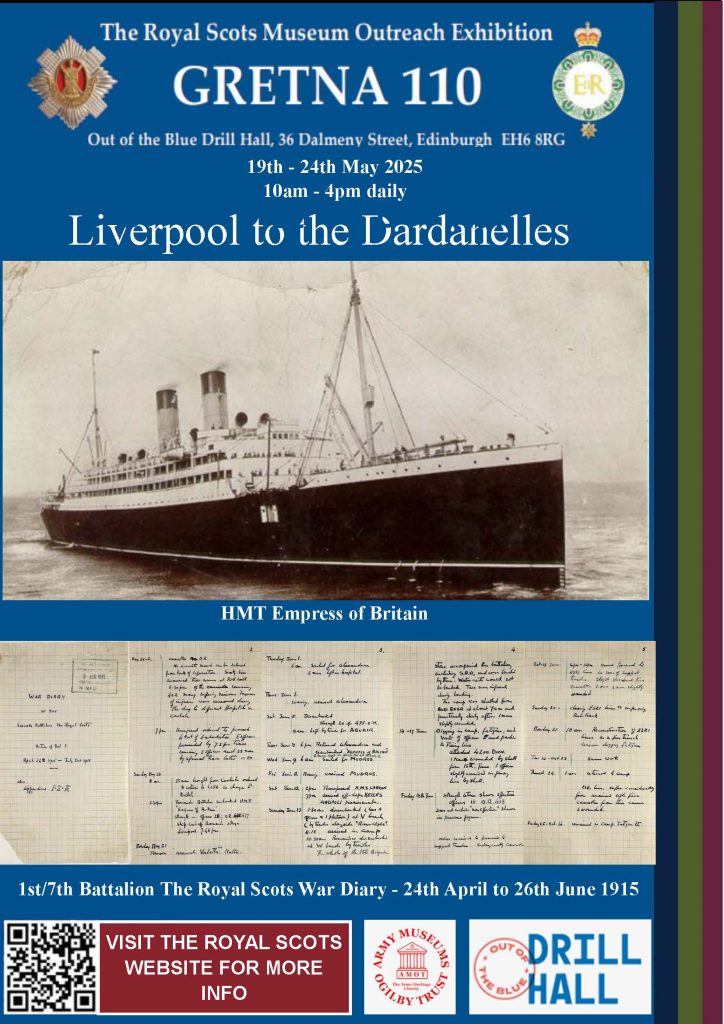

1st/7th Battalion The Royal Scots War Diary – From Liverpool to the Dardanelles

Sunday 23rd May

Remainder of the Battalion Embarked on HMT “Empress of Britain”. Strength – Officers 20; Other Ranks 477. Ship Cast Off from Liverpool 7.45pm.

Monday 31st May

Arrived Valetta, Malta in the forenoon.

Tuesday 1st June

Sailed for Alexandria at 6 am. (two Men left in Hospital)

Thursday 3rd June

Arrived Alexandria in the Evening.

Saturday 5th June

Disembarked Strength 20 Officers; 475 Other Ranks. Left by Train to Abukir.

Tuesday 8th June

Returned to Alexandria and Embarked “Empress of Britain”. (two Men left in Hospital at Abukir)

Wednesday 9th June

Sailed for Mudros.

Friday 11th June

Arrived at Mudros in the Morning.

Saturday 12th June

Transferred to HMS Carron at 2pm. Arrived off Cape Helles Gallipoli Peninsula at 7pm.

Sunday 13th June

1.30am disembarked (Less 4 Officers and 1 Platoon) at V Beach by Trawler alongside “River Clyde”. 4.15am arrived in Camp. 10.30am remainder disembarked at W beach by Trawler. (two men injured during landing). This camp was shelled from Achi Baba at about 7am and practically daily after. (one man slightly wounded).

Monday 14th – Thursday 17 June

Digging in Camp, fatigues, and visits of officers and parties to the Firing Line. Attached 42nd Division. (one man wounded by shell fire, 15th June, one officer slightly wounded in firing line by shell)

Friday 18th June

Strength 18 Officer; 458 Other Ranks. (does not include “Non-Effectives” shown in previous figures). Orders received to proceed to Support Trenches, subsequently cancelled.

Saturday 19th June

4pm – 10pm moved forward to ESKI lines in the rear of support trenches, slight shrapnel fire (one NCO and two Men slightly wounded)

#MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110 #Leith #Liverpool #Gallipoli #Dardanelles

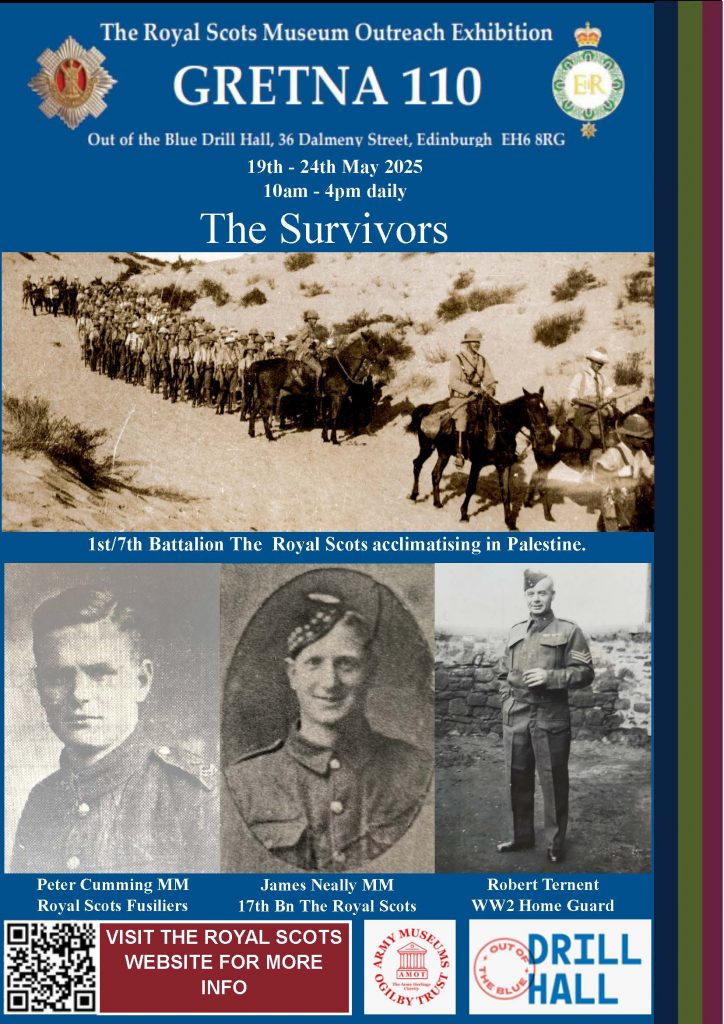

Survivors of the Gretna Rail Disaster

Of the half-battalion that was on the train, only sixty-two men survived unscathed. These survivors, including the Commanding Officer, continued on to Liverpool where 6 officers embarked, and sailed on the Sunday on HMT Empress of Britain with the other half of the Battalion that was on the other troop train. The remaining survivors, one officer and the 55 non-commissioned officers and men were sent back to Edinburgh. These survivors would later travel to the Balkans to join the battalion. Robert Ternent* (Musselburgh), landed in the Balkans on the 12 August 1915.

Over the months that followed soldiers who were injured in the crash and subsequently recovered and were considered fit for active service were later sent to serve with the Battalion in the Balkans. A few of those who took a bit longer to recover were also sent to serve with other battalions of The Royal Scots, and some were even attached to other Scottish Regiments, for example James Neally** (Armadale), who was injured with a bruised back, went overseas and served with the 17th Battalion The Royal Scots, and Peter Cummings (Leith), who was slightly injured, was subsequently attached to the 12th Battalion The Royal Scots Fusiliers.

* Robert Ternent would later serve in the Musselburgh Home Guard during the Second World War.

** James Neally was awarded a Military Medal, and was subsequently killed on 30 September 1918.

*** Peter Cummings was awarded a Military Medal and continued to serve with The Royal Scots Fusiliers in the 1920s.

#Gretna110 #Leith #Musselburgh #Armadale

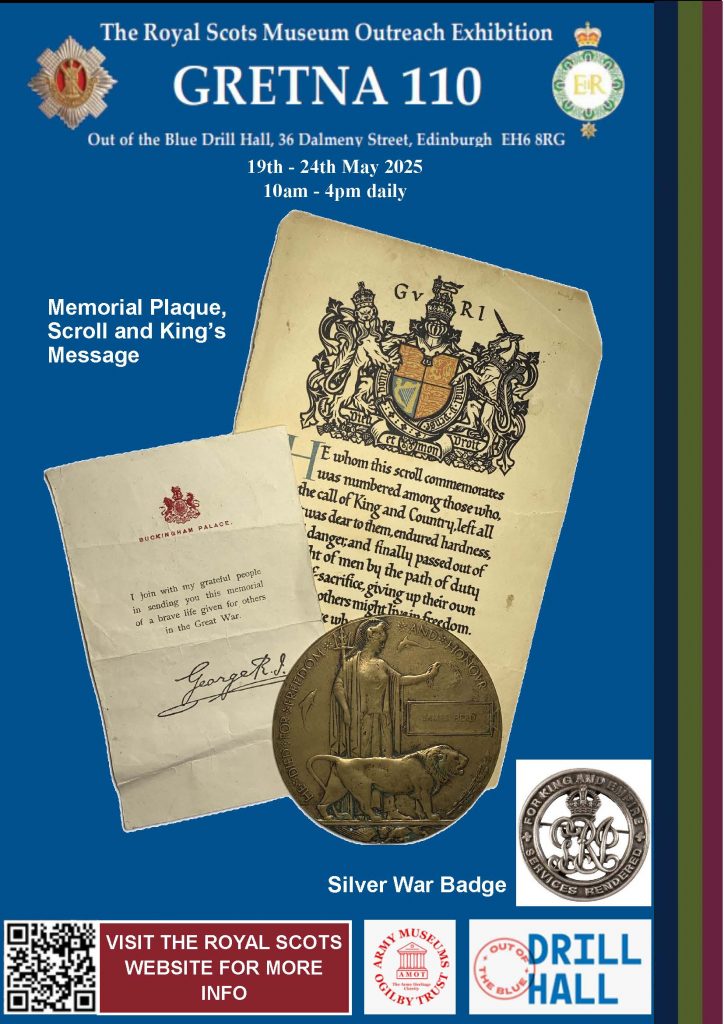

The Gretna Rail Disaster – Casualties

Next of Kin Memorial Plaque, Scroll and King’s Message

The Next of Kin Memorial Plaque is a bronze plaque approximately 11 cm in diameter with the name of the person who died serving with the British and Empire forces in the First World War. The Memorial Plaque was issued to the Next of Kin of the casualty along with the scroll, these were given to commemorate those who gave their lives and to acknowledge their sacrifice. They were intended to give the close family a physical memorial of their lost serviceperson. The Plaques and Scrolls were posted out separately, typically in 1919 and 1920, and a ‘King’s message’ was enclosed with both, containing a facsimile signature of the King. The immediate next of kin of all the Officers and Soldiers that died as a result of the Gretna Rail Disaster were eligible to receive the plaque and scroll. Men that did not serve overseas were not eligible for service medals.

Parliament – 13th February 1919

Captain W. BENN (Member of Parliament for Leith) asked the Secretary for War whether he is aware that a Scottish battalion en route to ship to Gallipoli in May, 1915, was involved in the Gretna railway disaster; and whether, in view of the fact that the battalion suffered very severely when thus under orders for overseas service, it would be possible to extend to the survivors the privilege of wearing the 1914–15 Star?

Mr. CHURCHILL

Entry on duty in a theatre of war is an essential condition for the award of every war medal, and I am afraid no exception can be made in the case of the men of the battalion mentioned by my hon. and gallant Friend.

The next of kin of those victims that died as a result of their injuries right up to 1921 (and possibly later) could still receive a plaque.

The memorial plaque features the figure of Britannia facing to her left and holding a laurel wreath in her left hand. Underneath the laurel wreath is a box where you will find the commemorated serviceperson’s name. The name was cast in raised relief on each plaque. In her right-hand Britannia is holding a trident. In representation of Britain’s sea power there are two dolphins each facing Britannia on her left and right sides. A growling lion stands in front of Britannia, with another much smaller lion under its feet, biting the German Imperial eagle. Around the edge of the plaque are the words “He (or She) died for freedom and honour”.

The scroll features a commemorative message underneath the Royal Crest, with the rank, name and regiment of the fallen soldier handwritten in calligraphic script, size 27cm x 17cm.

Silver War Badge

The Silver War Badge is a pin badge designed to be worn on civilian clothes after early discharge from the army. It was first issued in 1916, when it was also retrospectively awarded to those already discharged since August 1914. The Silver War Badge was awarded to all those men that were discharged from the Army as a result of the Gretna Rail Disaster. The main purpose of the badge was to prevent men not in uniform and without apparent disability being thought of as war dodgers. On the back of each badge is a unique number corresponding to the Silver War Badge Rolls, this means that each badge can be traced to an individual. The Silver War Badge Roll provides details of a specific unit that the soldier served in, giving his Regiment and Battalion, date of enlistment, date of discharge, and the cause of his discharge. The Cause of Discharge given for those discharged as a result of the Gretna Rail Disaster all read ‘Injury (Gretna)”.

#MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110 #Leith

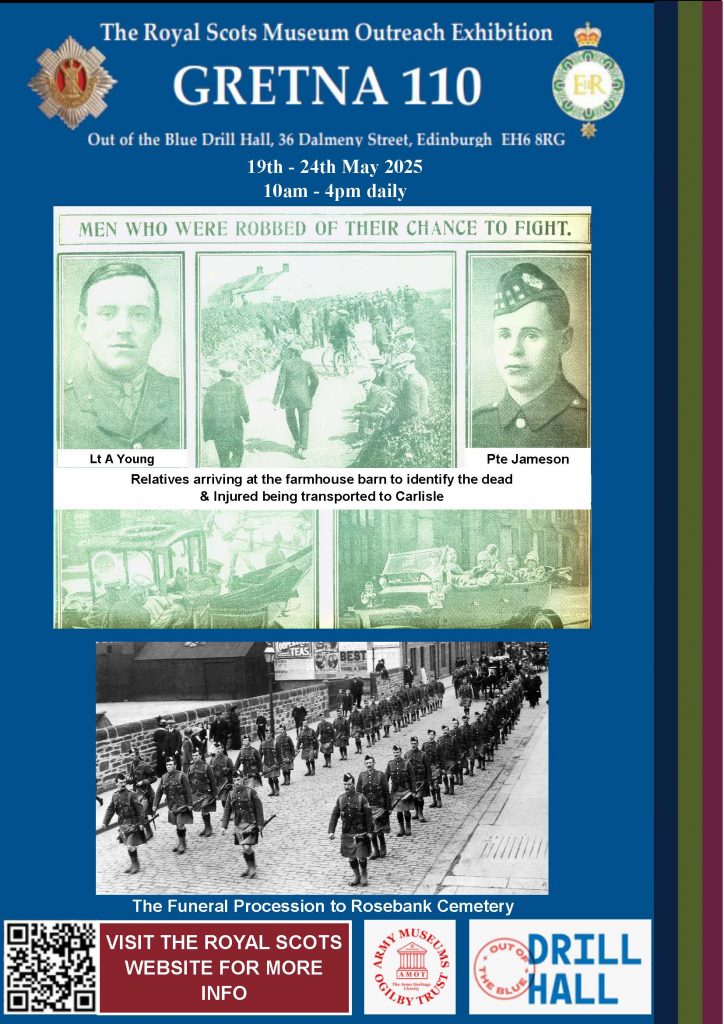

The Immediate Aftermath of the Gretna Rail Disaster.

The Gretna Rail Disaster was a devastating blow to the Battalion and to the whole population of Leith – it was said that there was not a family in the town untouched by the tragedy. This was made worse by the fact that, out of the 216 who died in the disaster, or soon afterwards from their injuries, only 83 were ever identified. The remaining 133 bodies could not be identified or were, literally, cremated within the firestorm of the wreckage.

Following the crash, the nearby city of Carlisle was overrun with unimaginable scenes of wounded soldiers bearing injuries that the civilians would only read about in newspapers, not see filing through their streets.

A report in the Scotsman on 24 May, 1915, reveals the vital role the city and people of Carlisle played in the aftermath:

Scotsman – 24 May 1915 – THE WOUNDED TAKEN TO CARLISLE

Carlisle was the most convenient centre for the reception of the injured soldiers, and though railway accidents had not been uncommon in this district, the strain upon the local resources in the grim hours of Saturday forenoon was unprecedented. […] The principal receiving station was the Cumberland Infirmary, where the wards were taxed to their utmost capacity. In cases where it was possible patients were sent to their homes, and beds were fitted up in every available corner, great energy being displayed by the officials in coping with the situation. The various Red Cross temporary Hospitals in the district also took the largest possible share in meeting the emergency, but it was necessary to requisition beds in a number of hotels within easy hail of the station.

About 180 injured soldiers were sent to Carlisle in the course of the forenoon. The first train, which reached the Citadel Station shortly after eleven o’clock, brought a number of the most serious cases. […] The injured continued to reach Carlisle for some time afterwards, and so hard-pressed were the ambulance attendants that it was no uncommon sight to see a man with his head swathed in bandages carrying bodily some comrade whose legs had been fractured. Under the circumstances the spirit displayed by the injured was wonderful. They had gone through an ordeal which would have tried the courage of the bravest, and their splendid fortitude called forth numerous expressions of admiration from the Red Cross Workers. Cheery words of thanks were tendered to those who rendered assistance, and examples of self-abnegation among the men themselves for the sake of giving a little extra comfort to more unfortunate comrades were numerous.

On Sunday 23 May, 107 coffins were taken back to Edinburgh and were placed in the Battalion’s Drill Hall in Dalmeny Street, off Leith Walk.

On the afternoon of Monday 24 May, 101 of these were taken in procession for burial in a mass grave that had been dug in Rosebank Cemetery, Pilrig Street, about a mile from the Drill Hall.

‘The route was lined by 3,150 soldiers [by comparison, the total figure on parade for Her Majesty’s Birthday Parade in London in 2013 was given as 1,000, including street liners], thousands of citizens stood shoulder to shoulder on the pavement; shops were closed, blinds were drawn, and the traffic stopped.’

For more information on the Quintinshill Train Crash, please see this page on our website – Quintinshill Train Crash | The Royal Scots

For more information on the WW1 battalions, please see this page on our website – https://www.theroyalscots.co.uk/1st-world-war/

#MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110 #Leith #Carlisle

THE QUINTINSHILL (GRETNA) TRAIN CRASH – 22 MAY 1915

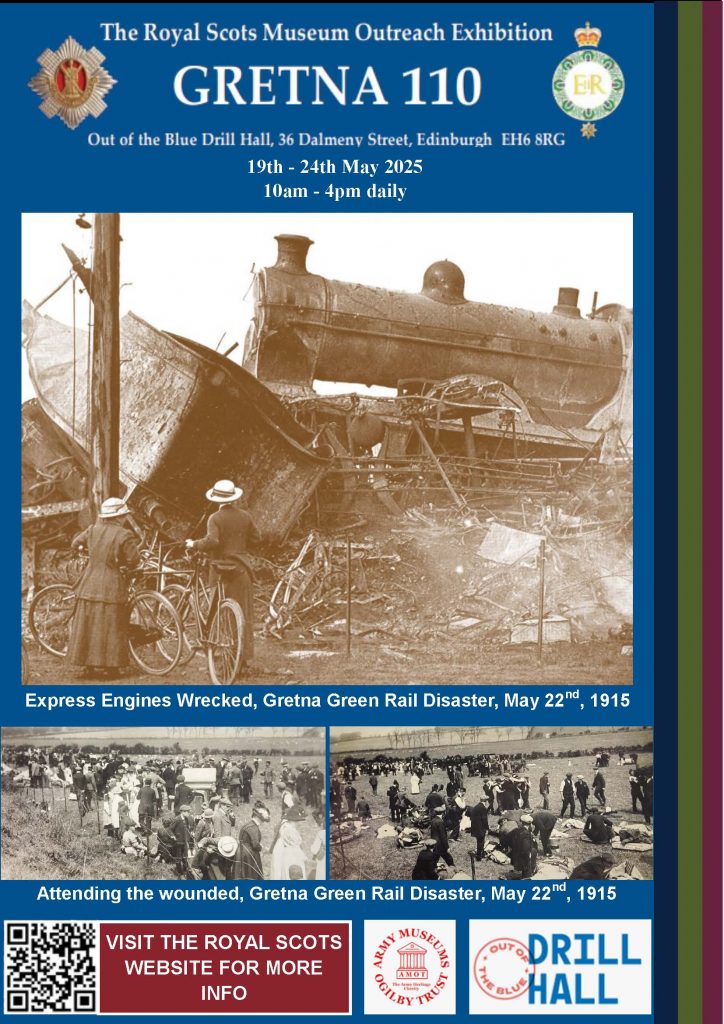

At 6.49 am on Saturday 22 May 1915 a Liverpool-bound troop-train carrying half (498 all ranks) of the 7th (Leith) Battalion, The Royal Scots (The Lothian Regiment) (7RS) collided head on with a local passenger train, which was stationary, facing north, on the south-bound main line at Quintinshill just north of Gretna, to allow a following express to overtake it. Normally the local train would have been held in one of the loops at Quintinshill but both of these were already occupied by goods trains. The troop train overturned, mostly onto the neighbouring north-bound mainline track and, a minute later, the Glasgow-bound express ploughed into the wreckage causing it to burst into flames. The ferocity of the fire, and consequent difficulty of rescuing those trapped in the overturned and mangled carriages, was compounded by the fact that most of the carriages were very old, made of wood and lit by gas contained in a tank beneath them. Between the crash and the fire a total of 216 all ranks of 7RS and 12 others, mostly from the express but including the driver and fireman on the troop-train, died in or as an immediate result of what was, and remains, Britain’s worst railway disaster.

7RS, had been mobilised in August 1914, and then employed on Coastal Defence duties on the Forth until April 1915 when they moved to Larbert, near Falkirk, to concentrate with 52nd Lowland Division before deploying to France. At the last moment orders were received changing the Division’s deployment to Gallipoli. The Battalion was meant to leave Larbert on 21 May to board the troopship Aquitania in Liverpool but she ran aground in the Mersey and the move was delayed twenty-four hours. At 3.45am on Saturday 22 May the first train left Larbert Station carrying Battalion Headquarters, A and D Companies. The accident happened at 6.49 a.m. The reaction to the accident was swift and spontaneous.

‘The survivors at once got to work to help their stricken comrades and soon the whole neighbourhood was alarmed, and motor cars from near and far hastened to the spot with medical and other help. The kindness shown on all hands will never be forgotten, especially by the people from the surrounding area and Carlisle who gave such valuable assistance to the injured. Their hospitals were soon overflowing, but all who needed attention were quickly made as comfortable as possible. Their Majesties The King and Queen early sent their sympathy and gifts to the hospitals.’Of the half-battalion on the train only sixty-two survived unscathed. These survivors, including the Commanding Officer, continued on to Liverpool where six officers embarked with the second half of the Battalion on HMT Empress of Britain and sailed on the Sunday, while one officer and the 55 soldier survivors were sent back to Edinburgh.

Your stories of the 7th Battalion, The Royal Scots wanted!

If you have family members or stories of the men that were involved in the Quintinshill Train Crash, we would love to hear from you. Please Email museum@theroyalscots.co.uk.

For more information on the Quintinshill Train Crash, please see this page on our website – Quintinshill Train Crash | The Royal Scots

For more information on the WW1 battalions, please see this page on our website – https://www.theroyalscots.co.uk/1st-world-war/

#MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110 #Leith

Pipe Bands of The Royal Scots

The pipe band was an integral part of every Scottish infantry regiment, and without it the regiments would lack a lot of what helps to create and impart the national characteristic and spirit.

Dating back to the earliest era of The Royal Scots, contemporary reports from the 1630s mention a pipe band in Hepburn’s Regiment of some 36 musicians and refer also to ‘the Scotch March’ believed to be the forerunner of Dumbarton’s Drums, the Regimental Quick March, played later by the Pipe Band. The oldest known image of pipers we have is in the painting of the destruction of the Mole at Tangier in 1684 showing four pipers on the Mole.

In the military history of Scotland, the pipes occupy an important and honoured place; they have stirred and inspired Scotland’s brave and gallant sons to great achievements on many a battlefield.

During the First World War in France & Flanders, Palestine, Salonica, and in North Russia pipers from The Royal Scots duly maintained the high traditions of their forebears.

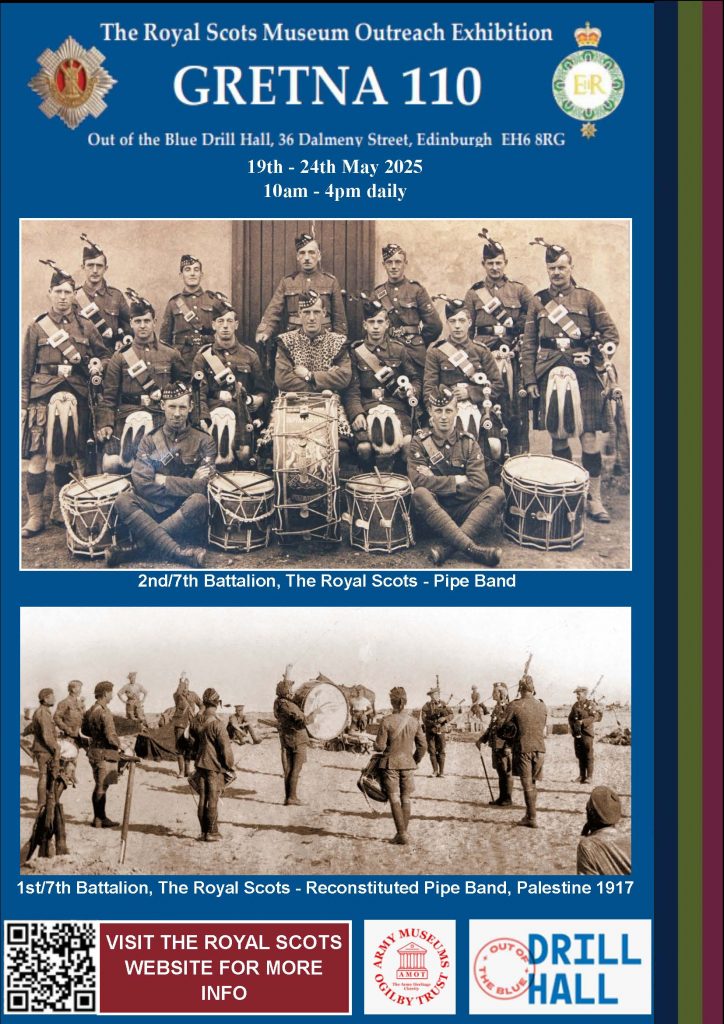

The 1st/7th Royal Scots Pipe Band

Unfortunately, the members of the 1st/7th Royal Scots Pipe Band were involved in the Gretna railway disaster, with the following members being killed and injured:

Killed – Pipe Major Gear, Piper G Smeaton, Piper A Nicol, Drummer J Malone, Drummer R Nicolson, Drummer A Grant, Drummer Simpson, Drummer A Murray, Drummer J Inglis.

Injured – Piper J Pearson, Piper T Clachers, Sergeant Drummer W Wilson, Drummer W Trainor, Drummer M Lawson

As a result, those pipers and drummers that did survive Gretna, and who subsequently went to Gallipoli in 1915 were employed in the ranks.

The 2nd/7th Royal Scots Pipe Band

On the outbreak of war Camelon & District pipe band was attached to the Falkirk Volunteer Training Corps. The band forged a close friendship with that of the 1st/7th Battalion which was encamped at Larbert, and after the Gretna railway disaster the band enlisted in a reserve battalion, with the view of eventually filling the gap created by the loss of the original 1st/7th Battalion pipe band.

After a period of service in home camps, the band was drafted to Egypt and joined the 1st/7th Battalion on its long, weary, and trying march through the Sinai Desert into Palestine.

Sunday, 25 March 1917 will ever remain a red-letter day in the memories of the pipers marking as it did the Battalion’s entry into Palestine to the appropriate tune of “Blue Bonnets Over the Border”.

2nd/7th Royal Scots Pipe Band Photograph:

Rear: Piper William Finlayson (Camelon), Corporal Drummer M Lawson (Edinburgh), Sergeant Drummer W. Wilson, (Leith), Lance Corporal Drummer W. Trainor (Edinburgh), Piper A. Russell (Bainsford), Lance Corporal Piper D. Brown (Camelon).

Middle: Pipe Major McLachlan (Camelon), Piper W Bruce (Stenhousemuir), Piper T Taylor (Camelon), Drummer R. Bow (Camelon), Piper A. Haxton (Camelon) – transferred to Lincolnshire Regiment and served in France, Piper D Sinclair (Camelon),

Front: Drummer A. McLachlan (Camelon), and Drummer J. Taylor (Camelon).

#Gretna110 #Camelon&DistrictPipeBand #MilitaryMuseumMonday

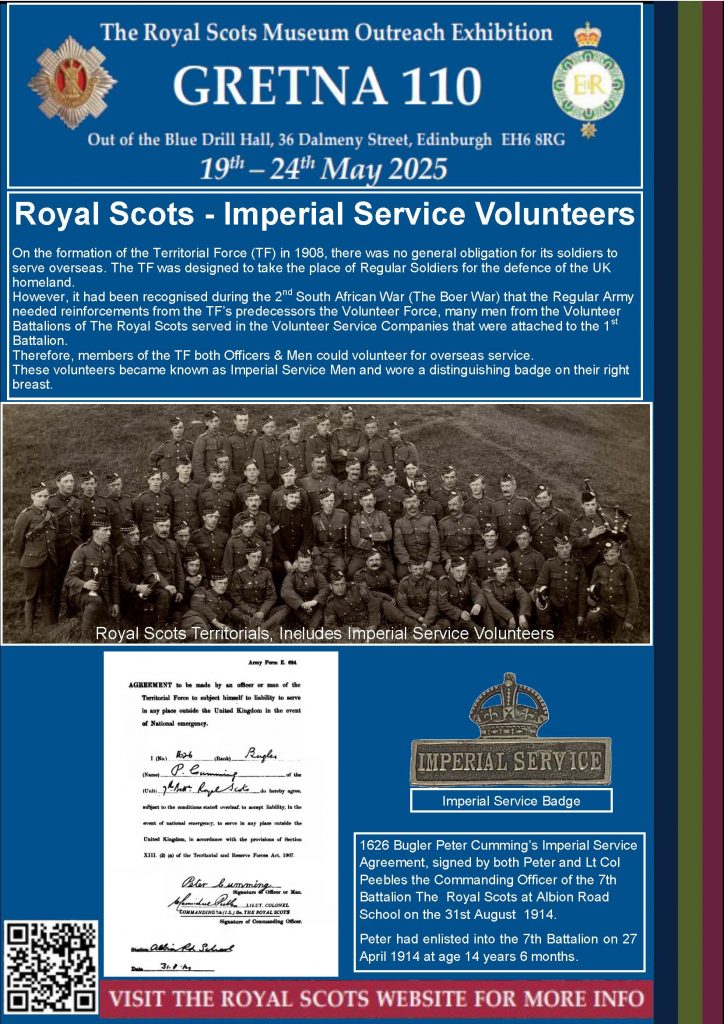

7th Battalion The Royal Scots – Imperial Service Volunteers

On the formation of the Territorial Force (TF) in 1908, there was no general obligation for its soldiers to serve overseas. The TF was designed to take the place of Regular Soldiers for the defence of the UK homeland. However, it had been recognised during the 2nd South African War (The Boer War) that the Regular Army needed reinforcements from the TF’s predecessors – the Volunteer Force. Many men from the Volunteer Battalions of The Royal Scots served in the Volunteer Service Companies that were attached to the 1st Battalion. Therefore, members of the Territorial Force both Officers & Men could volunteer for overseas service. These volunteers became known as Imperial Service Men and wore a distinguishing badge on their right breast.

From the battalions of the 7th Battalion The Royal Scots, the 1st/7th Battalion The Royal Scots became the Foreign Service Battalion, and the 2nd/7th Batalion The Royal Scots became the Home Defence Battalion. This prompted the transfer of the non-Imperial Service Men from the 1st/7th Battalion to the 2nd/7th Batalion, and likewise the transfer of Imperial Service men from the 2nd/7th Battalin to the 1st/7th Battalion. These transfers continued right up until the 20 May 1915, two days before the 1st 7th Battalion left for overseas service.

You can read more about The Royal Scots in the Great war on our Website here – 1st World War | The Royal Scots, and more about the Royal Scots Volunteer Service Companies in the Boer War here – AngloBoerWar

#Gretna110 #RoyalScots #MilitaryMuseumMonday

Your stories relating to the 7th Battalion, The Royal Scots wanted!

Despite being most commonly associated with Edinburgh and the Lothians, soldiers from across the country came to serve wearing The Royal Scots cap badge.

On the formation of the Territorial Force (TF) in 1908, there was no general obligation for its soldiers to serve overseas. The TF was designed to take the place of Regular Army for the defence of the UK. Soldiers from the TF could however volunteer to serve overseas, these volunteers became known as Imperial Service Men and wore a distinguishing badge on their right breast – The Imperial Service Badge.

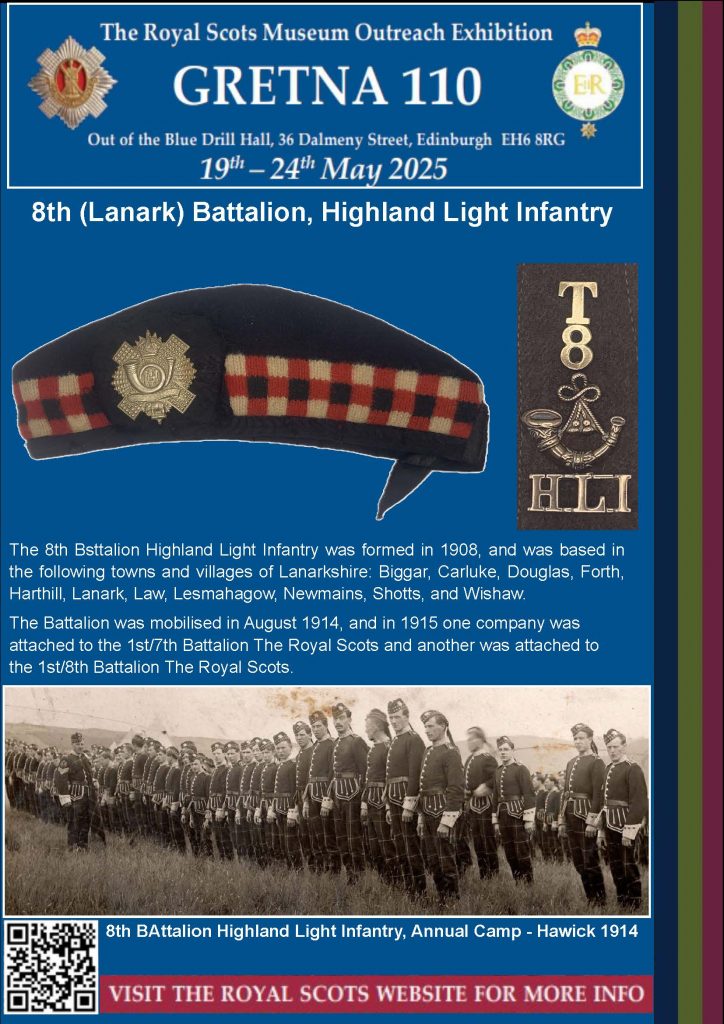

The 8th (Lanark) Battalion, Highland Light Infantry was formed in 1908, based out of Lanark but with company and platoon locations in the Lanarkshire towns of Biggar, Carluke, Douglas, Forth, Harthill, Law, Lesmahagow, Newmains, Shotts, and Wishaw. They mobilised in August 1914 at Lanark, part of the Lothian Brigade, and were charged to defend Scotland’s coastlines.

In order to make the 7th Battalion, The Royal Scots and 8th Battalion, The Royal Scots up to full strength before going overseas two companies of these ‘Imperial Service Volunteers’ from the 8th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry were attached, one company to the 7th Battalion, The Royal Scots and another company to the 8th Battalion, The Royal Scots. Those attached to the 8th Battalion, Royal Scots went to France in 1914 with the battalion, and those attached to the 7th Battalion, The Royal Scots went with the battalion to Gallipoli in 1915.

These 8th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry men were later formally transferred from the Highland Light Infantry to The Royal Scots. Many of them subsequently paid the supreme sacrifice and others received gallantry awards, including the Victoria Cross.

You can read more about The Royal Scots in the Great War on our website here – WW1 Battalions | The Royal Scots, and more about William Angus VC of the 8th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry, here – Gallantry Awards WW1 | The Royal Scots.

#Gretna110 #RoyalScots #HighlandLightInfantry #MilitaryMuseumMonday

PONTIUS PILATES BODYGUARD FOR THE 2025 RS MUSEUM OUTREACH EXHIBITION

PPBG is recruiting again now!

The 2025 RS Museum Outreach Exhibition, commemorating Gretna 110 will be held in the Out Of The Blue community centre in Dalmeny Street in Leith, formerly the Drill Hall of 7th (Leith) Battalion The Royal Scots 19-24 May 2025, with an Act of Remembrance at Gretna on 22 May 2025 and culminating in our annual Service of Remembrance at Rosebank Cemetary on the morning of Saturday 24 May 2025.

As at Dalkeith Palace in 2023 and Tynecastle 2024, PPBG Volunteer Guides are sought, in the same way as previously, for the RS Museum Outreach Exhibition at the Dalmeny Street Drill Hall. All the usual suspects, and others, are cordially invited to register interest by contacting wjblythe@hotmail.com at early convenience.

Watch this space for emerging details.

Up The Royals!

Jim Blythe

Your stories of the 7th Battalion, The Royal Scots wanted!

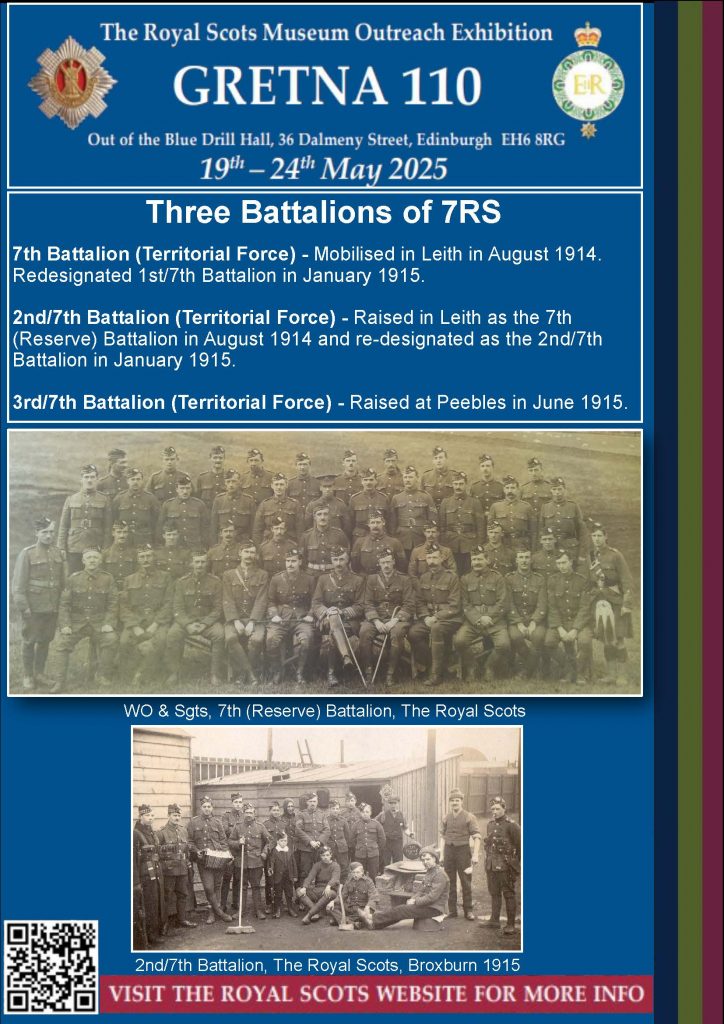

The three battalions of 7RS.

7RS was not just one battalion, but three. They were raised and served in different areas, from Galway all the way to Gallipoli. With the evolving nature of the Army during the First World War, including Kitchener’s famous ‘New Army’, battalions would be raised and quickly redesignated to allow for organisation in the rapidly expanding infantry.

7th Battalion (Territorial Force)

The 7th Battalion was formed in 1908 from the 1st Midlothian Rifle Volunteer Corps and was based in Leith. It was mobilised in August 1914, and subsequently redesignated as the 1st/7th Battalion in January 1915. The Battalion was listed for operations in Gallipoli in June 1915, the fateful move which saw the soldiers in headlines in the aftermath of The Gretna Rail Disaster of 22 May 1915. Those remaining in the 1st/7th continued to Gallipoli, before being transferred to Egypt in January 1916 and served there, and in Palestine, until April 1918. They went on to serve on the Western Front from April 1918 until the end of the war. They were reduced to cadre strength in March 1919 and returned home in May 1919.

2nd 7th Battalion (Territorial Force)

Raised in Leith as the 7th (Reserve) Battalion in August 1914, two large recruitment drives bolstered the numbers of this battalion. The first, in September, was held on the Easter Road Football Ground. The second was in October and targeted numerous towns throughout West Lothian. They were similarly redesignated in January 1915 as the 2nd/7th Battalion. During 1915 the Battalion served as part of the Scottish Coast Defences Brigade. Later it moved to quarters in Innerleithen and Walkerburn before joining 65th Division in Larbert in November 1915. It moved to Essex in February 1916 from where it despatched drafts for service overseas. In January 1917 the Battalion moved to Dublin, then to tented accommodation in County Galway and it later transferred to the Curragh. The Battalion’s service ended when it was disbanded in early 1918.

3rd/7th Battalion (Territorial Force)

Raised at Peebles in June 1915, the 3rd/7th Battalion received those members of the 1st/7th Battalion who had been injured in the Gretna disaster who were released as fit for service from hospital. The battalion moved to Innerleithen in November 1915 and then to Stobs Camp, Hawick in May 1916. Shortly afterwards it was absorbed into the new 4th (Reserve) Battalion, The Royal Scots, along with the 3rd/4th, 3rd/5th, 3rd/6th, 3rd/8th and 3rd/9th Batalions.

If you have family members or stories of the men that joined a Battalion of the 7RS, we would love to hear from you.

For more information on the WW1 battalions, please see our website at https://www.theroyalscots.co.uk/1st-world-war/ or contact museum@theroyalscots.co.uk.

#MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110 #Leith #WestLothian

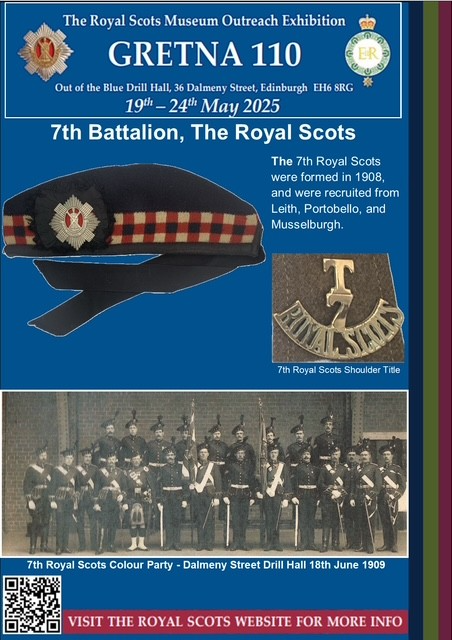

Your stories about the 7th Bn The Royal Scots wanted!

The Royal Scots has a long history with the Dalmeny Street Drill Hall, venue of our upcoming exhibition ‘Gretna 110’, found in the heart of Leith. The 7th Bn The Royal Scots was formed in 1908 with its Headquarters at Dalmeny Street in Leith.

If you have family members or stories of Leithers who joined the 7th Bn The Royal Scots, we would love to hear from you. Please contact museum@theroyalscots.co.uk for more information.

#MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110 #Leith

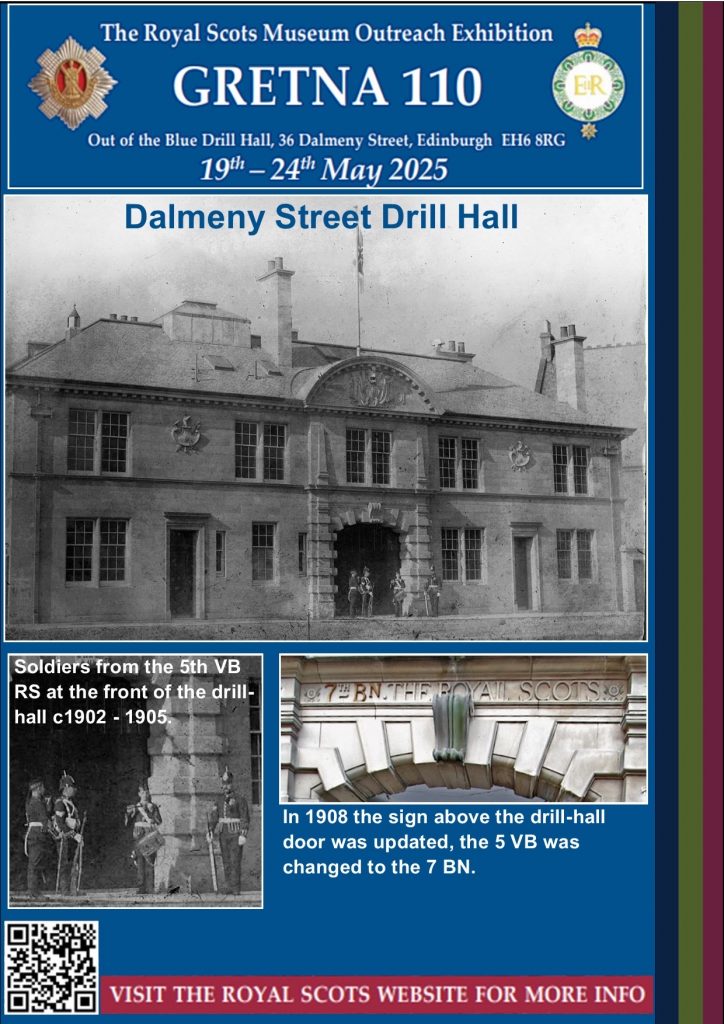

Your stories wanted!

The Royal Scots has a long history with the Dalmeny Street Drill Hall, venue of our upcoming exhibition ‘Gretna 110’, found in the heart of Leith.

During the 1850s and 1860s numerous Volunteer Units were raised in Scotland, then controlled by the Lord Lieutenants of Counties. In 1888 control was taken over by the War Office and they were grouped with regular infantry units. The Royal Scots expanded to include seven of these volunteer battalions.

One of these, the 5th Volunteer Battalion, had its headquarters and drill-hall in Stead’s Place, Leith, but these were burned down in 1900. In 1902 its new headquarters and drill-hall in Dalmeny Street, Leith Walk, were opened. This battalion also had its own rifle range, up to 1000 yards, at Seafield, near Leith

In 1908 these seven volunteer battalions were converted into seven new territorial force battalions. The 5th Volunteer Battalion thus became the 7th Territorial Force Battalion, with its Headquarters remaining at Dalmeny Street in Leith.

If you have family members or stories of Leithers who joined The Royal Scots, we would love to hear from you. Please contact museum@theroyalscots.co.uk for more information.

#MilitaryMuseumMonday #Gretna110 #Leith