The 1st Battalion had, by many standards, an unusual war.

At the outbreak of war the Battalion was in India. By mid-November it was back in Britain where it immediately mobilised. By 19 December it was at its war establishment of 30 officers and 972 soldiers. Three days later it marched from Winchester to Southampton where it embarked for Le Havre. By early 1915 it was in the front line in Flanders where it quickly learnt to adapt to the monotonous, yet dangerous, routine of trench warfare – holding the front line, being relieved, resting, providing working parties, relieving and holding the front line again. That routine was conducted against a backdrop of endemic sickness and violent death – a far cry from garrisoning the Empire of India.

From mid-April to late May the Battalion was engaged in the second Battle of Ypres. Although not involved in the fiercest of the fighting its casualties, nevertheless, totalled nine officers and 332 soldiers.

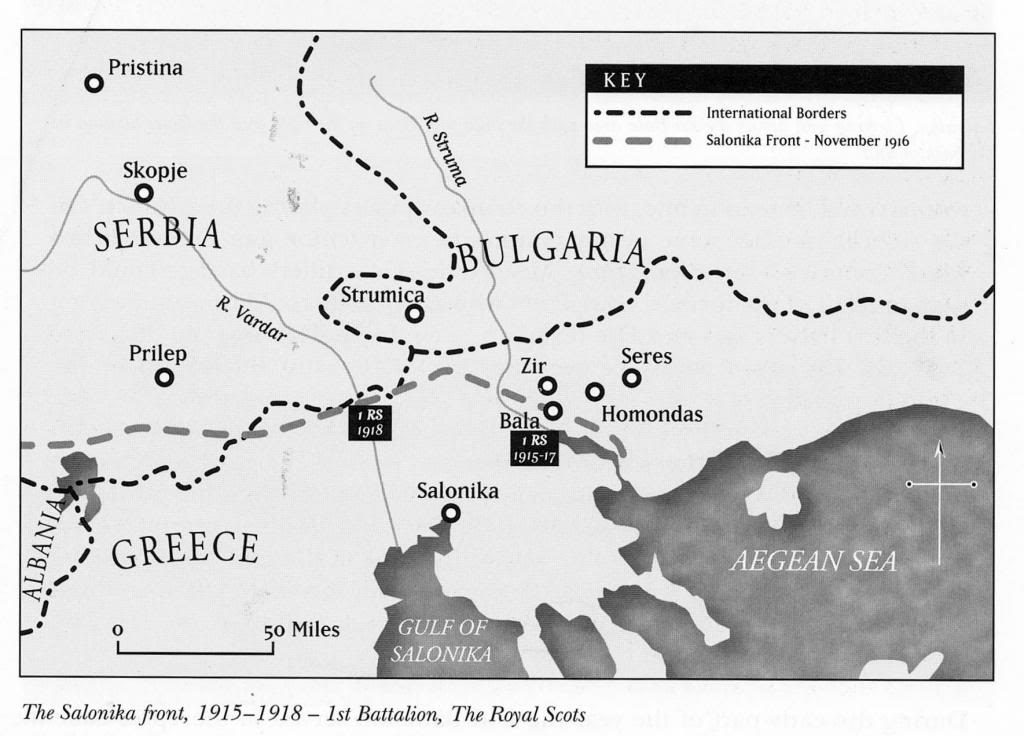

It continued to serve in France until late October. Thereafter it moved to Salonika in north-east Greece to help support Serbia, an ally, against the threat from Bulgaria, an opponent. Although it served in Salonika throughout 1916 it saw no action until September when it took part in the capture of the village of Zir in the valley of the River Struma, some 50 miles north-east of Salonika. The following contemporary account of the action at Zir illustrates the tactics used. These are reminiscent of the late 19th century and contrast starkly with the stalemate of the Western Front.

As dawn broke on 30 September we heard sounds of rifle fire from our immediate front but the support and reserve battalions continued to advance in Artillery formation, which meant that each company and platoon was deployed in sections in file maintaining its proper space in a square of about 400-500 yards on each side. The ground was level with no cover. The forward troops could be seen in line, with the company pipers playing the advance. On the right flank after some twenty minutes heavy machine gun fire was heard which continued for a long time. Meanwhile our artillery barrage could be seen in front of the forward companies whose bayonets could be seen flashing in the first light of the sun. The objective, some five miles away, the villages of Bala and Zir, could hardly be seen because of the dust thrown up by the exploding shells.

Behind us we could see on the heights spectators watching the battle. On our level we could see the artillery galloping into action, the guns being swung into position and the teams galloping back to a position of safety while the guns opened fire and the noise of the shells above our heads was at times quite deafening. There was also a cable wagon in front of the gun line galloping across the front with mounted linesman paying out the cable as they rode. It was in all a scene of the old South African type battlefield which no one who was there would ever forget.

Serre road, Salonika

1917 was much the same as the previous year. The Battalion remained on the front line in the Struma Valley but there was little action. Garrison duties were combined with patrolling and during rest periods a wide variety of sports were enjoyed. In stark contrast to the situation on the Western Front, the Battalion was able to enjoy football, hockey, athletics, boxing, all types of race-meetings, tennis and even golf, with two golf course being laid out partly under the direction of Lieutenant Gorrie of the Battalion. In the spring preparations were made for an offensive but, to the disappointment of the troops, that operation was cancelled. In the summer malaria became an increasing problem and the Battalion was withdrawn from the valley to the nearby foothills. That move allowed the Bulgarian forces to occupy villages in the valley but those were successfully raided in July and October and after the October raid the valley villages were reoccupied.

In April 1918, while still in the Struma Valley, the Battalion was relieved by a Greek unit. Thereafter it participated in an intensive training period before transferring westwards, in July, to the Vardar front where it replaced a French regiment. Initially there was a brief, but successful, struggle for the domination of no-man’s-land but, thereafter, there was little serious action other than raids and shelling.

At the beginning of September the level of activity was raised in an attempt to convince the Bulgarians that an offensive was about to be launched. In fact the activity on the Vardar front was part of an elaborate deception plan for an attack on another point. A diversionary attack in early September was successful but the new positions, which had recently been vacated by the enemy, had to be held for three weeks and throughout that period the Battalion was subjected to heavy shelling.

The Bulgarian defences were tested nightly by patrols and, on the night of 26/27 September, it was discovered that the enemy was vacating his forward positions. A general advance began at daybreak on 28 September, but by then the enemy was in full flight and Bulgaria, realising that Germany could no longer win the war, capitulated on 1 October. Although not on the scale of the Western Front the battalion’s losses on the Vardar were not inconsiderable. Three officers and 17 soldiers had been killed and four officers and about 100 soldiers had been wounded. Many others had succumbed to malaria. There was no great rejoicing when hostilities stopped. The Battalion, in common with other units, was put to work mending roads. It was an inauspicious end to what, for the Battalion, had been a disappointing campaign.

Being a regular Battalion, however, meant that its military duties did not cease with the end of the war. In December 1918 it sailed from Salonika through the Dardanelles to the port of Batum in Russian Georgia, at the eastern end of the Black Sea. From there it moved eastwards to Tiblisi where it provided guards on vulnerable points in the town. On 3 March 1919 it moved by train to Baku on the Caspian Sea to assist in taking over the Russian Caspian fleet from Bolshevist crews, but the latter had handed the ships over before the Battalion’s arrival. From Baku it returned to Tiblisi where demobilisation began.

Miners, students, professors and men over 41 returned home to be discharged and soldiers with less than two years of their engagement to serve were either discharged or posted home to join the 2nd Battalion. By the end of April the 1st Battalion had reduced to a strength of 15 officers and just 265 soldiers and shortly afterwards, it returned to Redford Barracks in Edinburgh. There it received recruits from the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion and platoons and companies were reorganised. In September 1919 it left for Burma where it served until 1922.

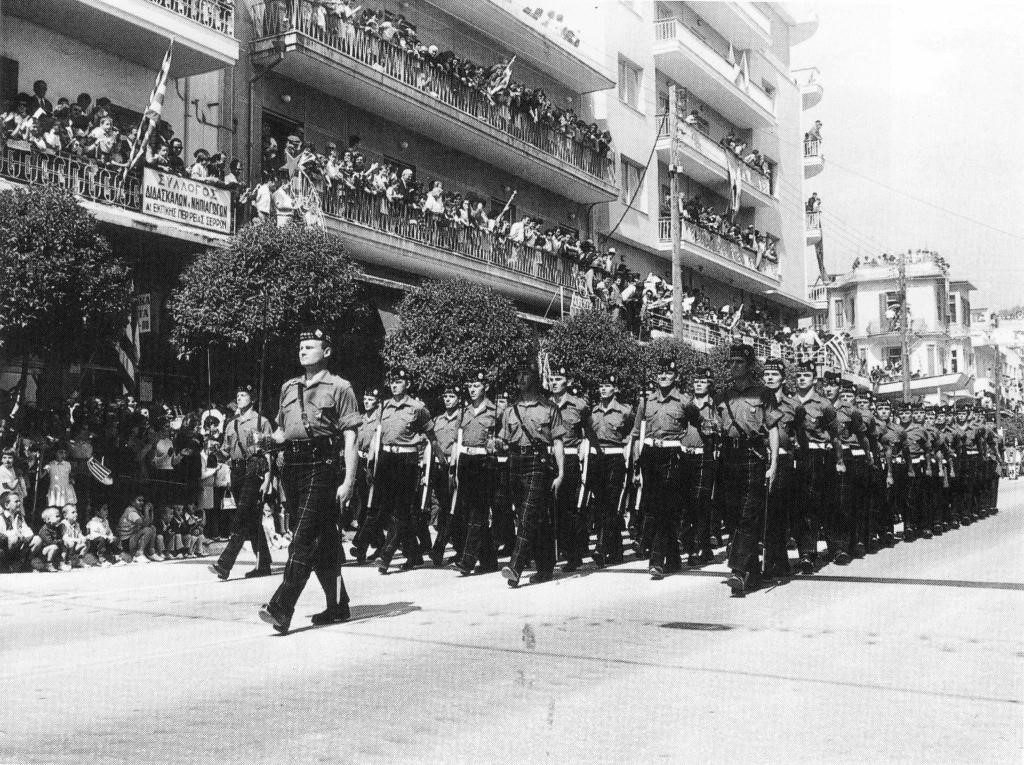

Postscript: In the early 1970s the then 1st Battalion had the role of the UK infantry battalion committed to the NATO Allied Command Europe Mobile Force (Land) or AMF(L) as it was known. This was a reinforced Brigade-sized force, drawn from a number of Nations, with deployment options on the Northern and Southern flanks of NATO. One of the options was North-East Greece deploying through Thessalonika (the modern name for Salonika). In 1971 and 1973 the Battalion deployed there on major Divisional-sized exercises, in cooperation with the Greek Army, operating over the same ground as the 1st Battalion had in 1915-18.

A Coy led by Maj JV Dent in Serrai 1971