Apart from those in B Echelon, very few officers and men of the 1st Battalion who had taken part in the heroic actions leading up to and at Le Paradis, defending the perimeter of Dunkirk, were taken off the beaches in 1940 There were the wounded who had been evacuated earlier in the fighting and a few who had got away partly by using their wits, partly by trusting to luck and going hell-for-leather for the coast. Those who did make it, less than 50 in total, were very quickly formed into the basis of a re-constituted 1st Battalion at Bradford, in Yorkshire, based on some 250 NCOs and men who were already Royal Scots and six hundred raw recruits. The next two years were spent on coastal defence and then training for the return to Europe. On 15 April 1942, however, the Battalion, again as part of the 4th Brigade, 2nd Division, alongside our old friends 1st Battalion The Royal Norfolk Regiment, who had also been re-constituted after Le Paradis, sailed from Glasgow en route to India to join the defence of India against the Japanese who were by then advancing up through Burma.

In early March 1943, after considerable training, and a number of false starts, the Battalion was committed to action in the Arakan. The action there was not successful and the British and Indian force withdrew back to Chittagong in India.

During the last week of May 1943 the 1st Battalion moved from Chittagong by train to Ahemednagar, east of Bombay, where it rejoined 2 Division. Thereafter, for a ten day period, the whole Battalion, having taken 550 sick in the Arakan, mainly from malaria, was subjected to an intensive period of anti-malarial medication during which no strenuous training, or exercise, was carried out. Shortly afterwards it received reinforcements and undertook a comprehensive period of re-training. At the end of January 1944 it moved to Belgaum in the central Ganges plain where it was possible to embark upon intensive jungle training. The feature of jungle training loathed most by the Jocks was the presence of leeches as Sergeant Easton recalled.

We had puttees instead of gaiters because the place was alive with leeches. You even had to put grease on the eyeholes of your boots to save them going in, and even then they got in. You felt them getting into your flesh and when you took your puttees off at night your trousers were filled with leeches that had had their fill and were lying in the bottom of your trousers.

In early March 1944 the Japanese launched a major offensive westwards from the Chindwin towards Kohima and Imphal. Their initial aim was to seize Imphal in order that it could be used as a supply base for the invasion of India. The British and Indian troops operating to the west of the Chindwin fell back on Imphal and the village of Kohima, which they were determined to hold as their strategic importance was fully realised. The nature of the countryside on the Indo-Burmese border, an extreme mix of almost trackless mountains and jungle, made the possession of motorable roads essential for success. The British and Indian forces were supplied from the railhead at Dimapur via the road through Kohima to Imphal. If that road was cut men and pack animals had to be re-supplied by air.

It was against that background that the 1st Battalion, along with the remainder of 2 Division, was ordered to move to Calcutta by train and then to Dimapur by air. The Battalion moved at a strength of forty officers and 830 soldiers. For many this was their first experience of flying. Kohima’s garrison consisted of just 1,000 troops and it was being threatened by a Japanese force of 12,000. The Japanese closed the Dimapur-Kohima road, however, just a few miles to the north-west of Kohima on 7 April, about a week before the Battalion was complete in Dimapur.

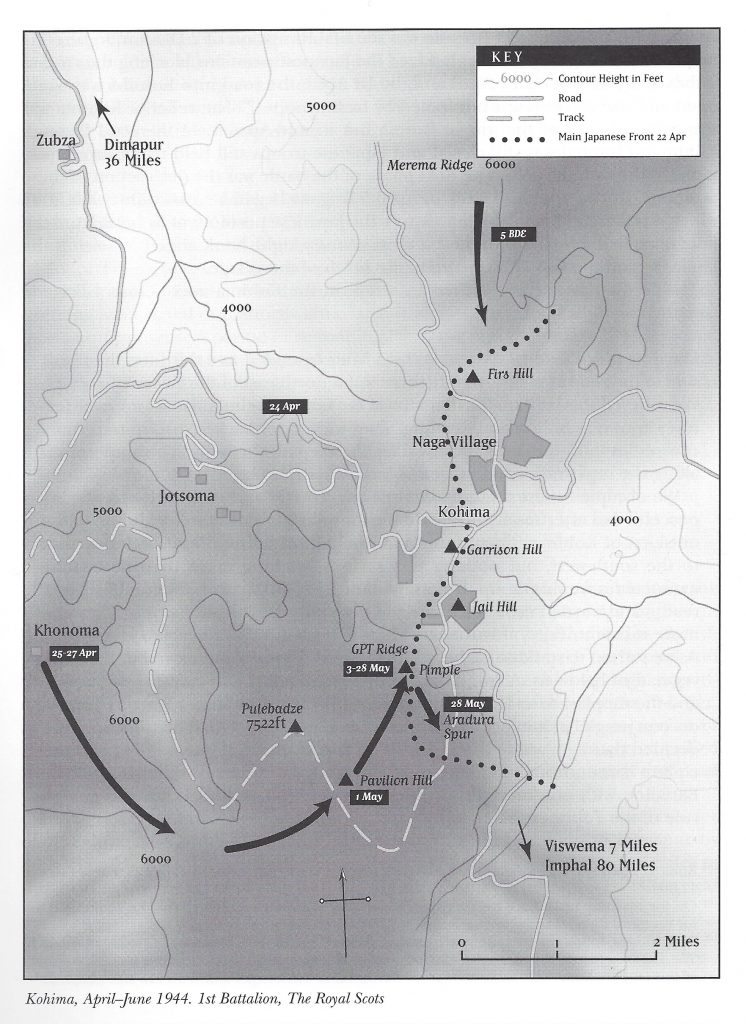

5 Brigade was the first formation of 2 Division to be committed to the relief of Kohima. It seized the Japanese positions blocking the road at Zubza and Jotsoma on 14 April and, by 18 April, with the Garrison Commander estimating that he could hold our for no more than a further twelve hours,the road into Kohima was again open and the garrison was reinforced by fresh troops. The relief of Kohima was the turning point of the war in Burma but in mid-April 1944 the road through Kohima to Imphal was still closed and Japanese troops still held many strong positions in the Kohima area. The next phase of the battle was the destruction of these positions. During the third week in April 5 Brigade began a cross-country left hook which was designed to enable it to attack the Japanese positions at Kohima from the north, while 4 Brigade mounted a cross-country right hook aimed at seizing the Japanese positions on GPT Ridge, to the south of the village.

The 1st Battalion, however, was in action in the Kohima area before 4 Brigade launched its right hook.

Our first task was to take over two hills, later extended to a third, on the north side of the road at milestone 32 [three miles north-east of the village of Zubza]. We relieved the 1st Battalion The Royal Berkshire Regiment and took over features known as Bolton and Reading. They were razor-backed, precipitous spurs covered in thick jungle. A narrow track that kept to the highest ground wound along the tops and ended in a close-built wooden village.

We occupied these features without any trouble and dug in. It was all very peaceful that afternoon. One could see for miles across the valley and on to the outskirts of Kohima. There was some shelling from one of our batteries away to the south-west, but nothing very serious, nothing more than peace-time manoeuvres would put up. It reminded one of all the war books one had ever read – and warned us. Then came the evening, and the jungle noises became more insistent. Previously they had hardly broken through our own activities.

As we started to stand-to we heard them clearly. Something moved in the thick vegetation below us. A twig broke and then another. Our nerves were taught and the simplest sounds appeared more menacing than anything we had heard on our jungle training. But the night passed quietly. Once or twice a sentry decided that a Japanese battalion was on top of him, but our training and discipline came to our aid. There was no false alarm and morning found the Battalion with one more lesson learnt: never fire at night. It was the golden rule of the Fourteenth Army.

There were soon other, more important, lessons to be learnt.

A day or two after we had settled in came our first contact with the enemy. Major Russell, commanding D Company, had sent a patrol along a track to the south-east. It bumped the enemy, had some casualties and withdrew. The remainder of the platoon was pushed in and then the whole company. The Japs were well dug-in on a steep cliff. We could not see them, but they could see us. We probed all round them, lost about a dozen men and then the company withdrew. Our losses had not been heavy, but we had the unsatisfactory feeling that we had lost some very good men, and we could not swear to having killed a single Jap. It was our first attempt to turn the little yellow rats out of their holes without supporting fire, and our last. Just another jungle warfare lesson learnt.

The lesson was quickly learnt, however, and the Jap position was subjected to artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire. Initially all that effort seemed to be of no avail as a second attack was again met with determined resistance and had to be called off. The recipe was repeated and this time the results were different.

On the road to Kohima. Major Hayward, Second in Command of the 1st Battalion (centre) with Captain Currie, Adjutant, on the right

Next morning Lieutenant Darling, patrolling down to the enemy position, reported it clear of Japs. We went down and found it devoid of life, but by no means clear of Japs. There were considerably more dead Japs than our total casualties, and that cheered us up enormously. We saw what a shambles the place was. The reverse slope where our mortars had got busy seemed particularly damaged. There must have been a company headquarters and a first aid post there and both had received direct hits. Sergeant Smail dug up one grave with twenty dead Japs in it. All had been wounded and then beheaded before their ‘comrades’ withdrew. This put a very different complexion on the battle. We realised that though we may not appear to inflict casualties on the enemy we were doing so the whole time. It was a good lesson and we remembered it throughout the campaign.

The Battalion’s casualties for April 1944 were fifteen soldiers killed, two officers and thirty-five soldiers wounded and one soldier missing.

On 24 April the Battalion moved forward on the main road towards Kohima to a position north of the village of Jotsoma. From there, on the following day, it moved by a mixture of vehicle and march route up to the village of Khonoma from where it began its cross-country approach to Kohima on 27 April, but it did not arrive at GPT Ridge until 3 May. It was a hazardous journey.

The march was probably not more than thirty miles and it was expected to take about five or six days. To those who do not know the country this sounds a fairly easy feat. But it was not. The track had been made by the Special Service Company under Major MacGeorge, The Royal Scots. It was a single-file march and in parts ropes had been put down to drag oneself up the sheer precipices. Naga porters helped with some of the heavier equipment and with rations, but no air drop was attempted, firstly because there was no possible dropping zone, and secondly, to maintain surprise. Mules, of course, were out of the question. It was simply a matter of climbing to the top of a ridge and slithering down the other side on one’s haunches. The ridges varied in height from hundreds to thousands of feet, and the temperature in the valleys and on the tops varied accordingly. It was not a march in the accepted sense of the word. It was a climb, pure and simple, which was in direct contrast to our language, which was neither.

During the flanking move there was some action on Pavilion Hill on 1 May. A group of unarmed Naga porters was ambushed by the Japanese. Not surprisingly they dropped the rations they were carrying and fled. A platoon of A Company,anticipating that the Japanese would return to retrieve the rations, mounted its own ambush at the same spot. The Japanese duly returned and the ambush was sprung leaving three dead. Later in the day the Japs mounted attacks on Pavilion Hill which initially was held by just two platoons of A Company and the Manchester’s Machine- Gun Platoon, but later reinforced by the arrival of C Company.

Fortunately the Jap decided to attack from the south-east and walked, or rather climbed, straight into A Company’s LMGs. He withdrew after about twenty minutes and left us very much master of ourselves and of the situation. Just then Major Menzies arrived with C Company and Somerville’s platoon rejoined after their successful ambush on the Japanese on 1 May. That put a very different complexion on the affair and the next attack, which was launched just before dusk, was beaten off with considerable slaughter. Fortunately for us, it seems it was a Jap habit to announce his intention of attacking by screams of ‘Banzai’ and other encouraging noises, which always gave us ample time to prepare for him. Another of his habits which militated against success was his invariable practice of reinforcing failure. From dusk to 11 pm he put in an hourly attack at exacdy the same place, in exactly the same way with exactly the same result. It is true that on one occasion he managed to get two or three men inside our position, but they were immediately dealt with by Lieutenant Black and Lance Corporal McKay. Our total casualties did not amount to half a dozen and we picked up and buried seventeen of the enemy in the immediate vicinity of our posts. That there were many more nearby was proved by the fact that a few days later another unit was unable to stay on Pavilion Hill owing to the smell of carrion.

The attack on GPT Ridge was led by The Royal Norfolks with The Royal Scots in support. Surprisingly the attack caught the Japanese unawares and the Norfolks drove forward to within 100 yards of the end of the ridge with the 1st Battalion following them closely. The two battalions were surrounded by Japanese, but in such thick country it was possible for patrols to get through to the rear without being discovered. Both battalions quickly set about consolidating their positions with dogged determination.

We arrived on 3 May and I suppose we were there about a week. For the first day or two we were continually sniped and harried by an active enemy who was fighting on his own ground and knew every track and game trail. But gradually we got the better of him. First we blitzed the area between ourselves and the Norfolks and joined up the [battalion] boxes. Then we started counter-sniping, at which we had considerable success. RSM Brunton was a particularly keen and efficient shikari (Hindi word for hunter).

A patrol on the approaches to Kohima

He discovered a Japanese water point and sat over it. I have forgotten what his exact bag came to, but it was a welcome addition to the daily total. We also laid some very successful ambushes around our position. The Pioneer Platoon was notably successful and one of their ambushes so annoyed the Japs in the big bunker to our rear as to make an attack upon us. This was more noisy than effective and was easily repulsed. An immediate counter-attack by the Carrier Platoon, in which Sergeant Dick greatly distinguished himself, caught the enemy just as he was reforming. Our bag for that day, I remember, was thirty-one counted Jap bodies.

Sergeant Syme, who was a Section Commander in the Carrier Platoon, having been forced to leave their vehicles behind and now forming Patrol Platoon, recalled the part he played in the action around Kohima on 5 May.

Once the Japs began taking pot shots at A Company, and some of A Company began to get a wee bit shaky, so the Patrol Platoon was sent for and out we went – the whole Platoon. It just so happened that I was the leading Section to go, so that the rest of the Platoon could stretch out behind me. I’ll tell you, I went along there and there was nothing that I didn’t see. We stopped when we were in line and we turned and we had a wee rise up to where they were [the Japanese] and we went up over the rise. I had my Bren gunner killed, that was the first man I’d ever lost.

The Japanese, however, refused to be driven from their positions and there was heavy fighting involving the Norfolks and C Company of The Royal Scots to try to drive them from a major bunker on a feature known as the Pimple. The enemy held out for nine days in that position which was eventually cleared by B Company after it had been subjected to direct fire from tanks at a range of thirty yards.

The next objective was to clear the Japanese from their positions on Aradura Spur which was attacked on 28 May. Again the enemy’s resistance was determined and casualties were so high that the attack had to be called off. Once again Sergeant Syme was involved in the action.

The Japs were falling back from Kohima, and this next hill, [Aradura Spur] we patrolled it daily for a week before putting in an attack. Although we had patrolled the area daily we lost sixty odd men in the attack, killed (17), wounded or missing and Christ knows where they [the Japs] were because we never saw them. We couldn’t stay on top, we just had to come back off it. The next time we went there was nobody there, they were away!

By then, however, the Japanese were feeling the pressure of the incessant attacks being mounted throughout the whole of the Kohima area. Furthermore their morale was being undermined by the failure of their supply system to provide them with food. On the last day of May 1944 the local Japanese commander decided, against his orders, that he would have to withdraw. That movement started in early June. The battle for Kohima was over; it had lasted for sixty-four days and witnessed some of the fiercest fighting of the war. In May the Battalion had lost one officer and thirty-six soldiers killed, seven officers and 115 soldiers wounded and nine soldiers missing. Imphal was still cut off but, as the Japanese withdrew, the British and Indian troops were free to follow them south down the road to Imphal.

The final major battle of the Kohima campaign for the 1st Battalion took place at the large village of Viswema, twelve miles from Kohima and seventy-five miles from Imphal, on 6 June. The Lancashire Fusiliers were the lead battalion of 2 Division with The Royal Scots immediately behind them. The initial attack by the Fusiliers was repulsed and both battalions attacked in concert the following morning. Again Japanese resistance was determined but the attackers managed to break into the enemy’s perimeter. The battle lasted three days and casualties were heavy.The position was eventually cleared by a set piece attack by the 7th Battalion The Worcestershire Regiment. Once Viswema fell the operation became an advance in contact and, although there were some stiff local actions, 2 Division was able to make steady progress towards Imphal. On 21 June the troops thrusting south from Kohima met up with those pushing north from Imphal. The Japanese advance into India had been defeated. The Battalion’s losses during the Kohima campaign were two officers and seventy-six soldiers killed, fifteen officers and 189 soldiers wounded and four soldiers missing. On 24 June, at the end of the campaign, the Battalion’s strength was twenty-six officers and 512 soldiers – the difference of some seventy all ranks from the emplaning figure in early April being accounted for by sickness.

Postscript. While the 2nd Division set about erecting a Divisional Memorial to those who had fallen in the epic struggle to relieve Kohima and open the road to Imphal, the 1st Battalion were equally determined to additionally commemorate their own. This Memorial was designed and constructed by The Royal Scots themselves under the supervision of a small committee. It was made of local stone and wood and was erected by the Pioneer Platoon. The Monument is sited at Kennedy Hill, on the Aradura Spur, and was unveiled by Lieutenant Colonel Masterton Smith, who had fought throughout the Battle and was now the Commanding Officer, on 25 November 1944. The Monument, overseen by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, is now surrounded by local housing but (in 2017) was reported as being in good order and carefully looked after by the family living around it.

Dedication of 1st Battalion Memorial, Aradura Spur, Imphal, 25 November 1944. The padre is the Reverend Chricton Robertson

When you go home

Tell them of us and say

For your tomorrow

We gave our today

The Kohima Epitaph