THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

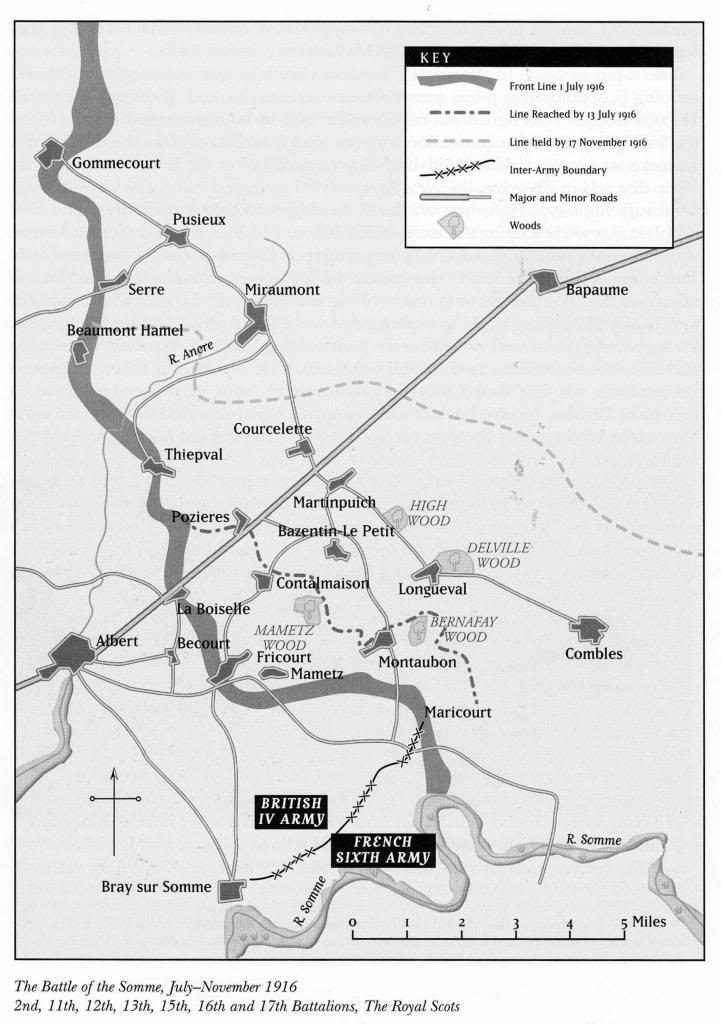

By the summer of 1916 the British Army in France had grown to some fifty-eight divisions, in all some 1.5 million men. Haig, who had taken over as Commander-in-Chief from Sir John French in December 1915, now had the manpower that he had lacked earlier and, at 7.30 am on 1 July, eleven divisions, nine of them New Army divisions, advanced simultaneously against the German positions on the north bank of the Somme. By nightfall British losses were over 57,000, of whom nearly 20,000 were dead. Some gains were made by the attacking forces on the right (southern) flank, but elsewhere the attack had stopped in its tracks. The first day of the Somme, in terms of casualties, remains the blackest day in the history of the British Army.

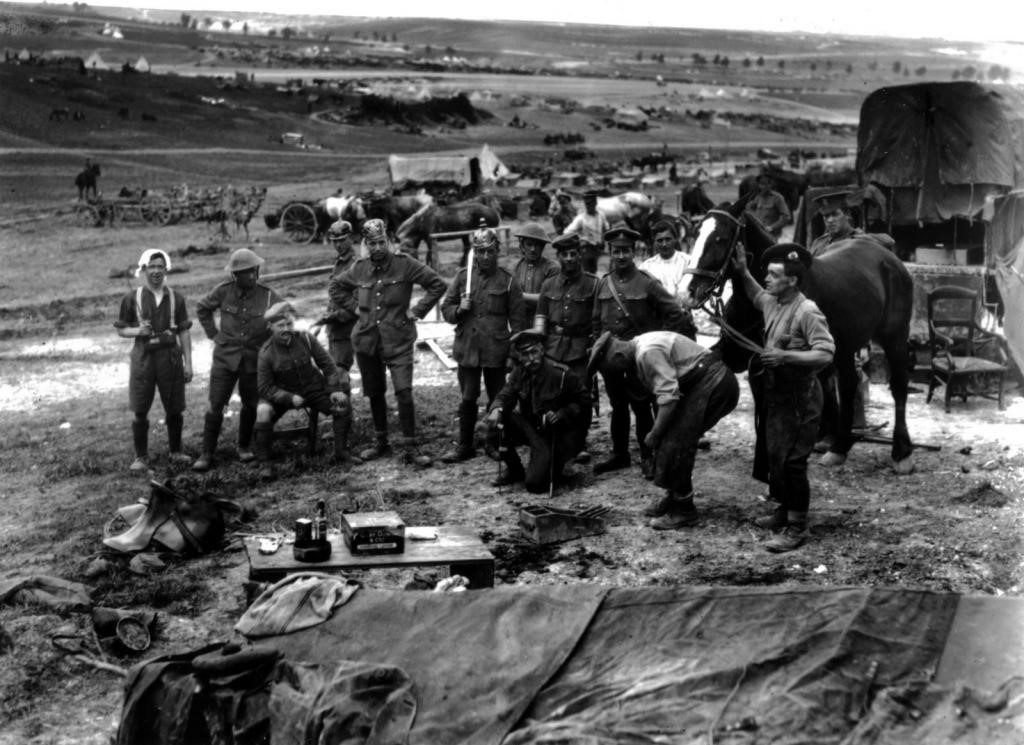

9 RS in wet weather

The object of the Somme offensive was to capture the low plateau that lay between the Somme and the Ancre. The fighting, although not in Haig’s original plan, fell into three phases. During the first phase, which lasted until mid-July, the southern crest of the plateau was seized from Delville Wood to Bazentin-le-Petit. The second phase raged from mid-July to early September during which the British managed to hang onto their gains, despite almost continuous German counter-attacks. By September the Germans had accepted that they could not dislodge the British and began to prepare the Hindenburg Line, some fifteen miles to the east of the front line of 1 July. Against that background the British were able to occupy the whole of the plateau during phase three, which lasted from early September until early November, when the onset of winter rains brought the campaign to a close. All six Royal Scots New Army Service Battalions took part in the campaign as did the 2nd Battalion and the 8th and 9th Territorial Battalions. This paper will, however, only concern itself in detail with the story of the New Army Battalions.

The Royal Scots Battalions at The Somme – 1 July-1 November 1916

Background

The following nine Royal Scots Battalions were involved in The Battle of The Somme:

2nd (Regular), 8th (TF), 9th (Highlanders) (TF), 11th and 12th (K1), 13th (K2) and 15th, 16th and 17th (K3/K4).

The 2nd had deployed to France in 8 Bde, 3 Div, with the BEF on 14 August 1914.

The 8th landed in France on 5 November 1914, the first Scottish-based Territorial Force (TF) unit to land there and, along with only two other TF Battalions, was judged to be fit for immediate deployment, joining 22 Bde, 7 Div on 11 November. The Battalion became the Pioneer battalion of 51 (Highland) Div in August 1915.

The 9th (Highlanders) landed in France on 26 February 1915 and, by the Somme, were serving in 154 Bde, 51 (Highland) Div.

The 11th and 12th, raised in Edinburgh in August 1914 as part of Kitchener’s first army of wartime volunteers (K1), landed in France 9-12 February 1915 as part of 27 Bde, 9 (Scottish) Div.

The 13th, raised in Edinburgh in September 1914 as part of K2, landed in France 7-13 July 1915 as part of 45 Bde, 15 (Scottish) Div.

The 15th (1st Edinburgh) (Cranston’s), raised in Edinburgh in September 1914 as part of K3, and including 300 Scottish volunteers from Manchester, landed in France 8 January 1916 as part of 101 Bde, 34 Div.

The 16th (2nd Edinburgh) (McCrae’s), raised in Edinburgh in November 1914 as part of K3, landed in France on 8 January 1916, alongside the 15th, as part of 101 Bde, 34 Div.

The 17th (Rosebery’s Bantams), raised in Edinburgh in February 1915 as part of K4, landed in France on 1 February 1916 as part of 106 Bde, 35 Div.

The Battle

The operational experience of the individual battalions directly reflected the length of time they had been in France. By 1 July 1916 the 2nd, 8th and 9th Battalions had all been through the early battles and those of 1915 while the 11th, 12th and 13th had all been at Loos in 1915. By contrast the 15th, 16th and 17th had had a relatively straight forward introduction to the Western Front, from January 1916, during which companies were attached, in rotation, to more experienced battalions serving in the trenches in relatively quieter sectors. This changed, however, in April when the 15th and 16th Battalions were withdrawn from the line to put in some strenuous training in preparation for the Somme to be followed, in mid-June, by the 17th Battalion.

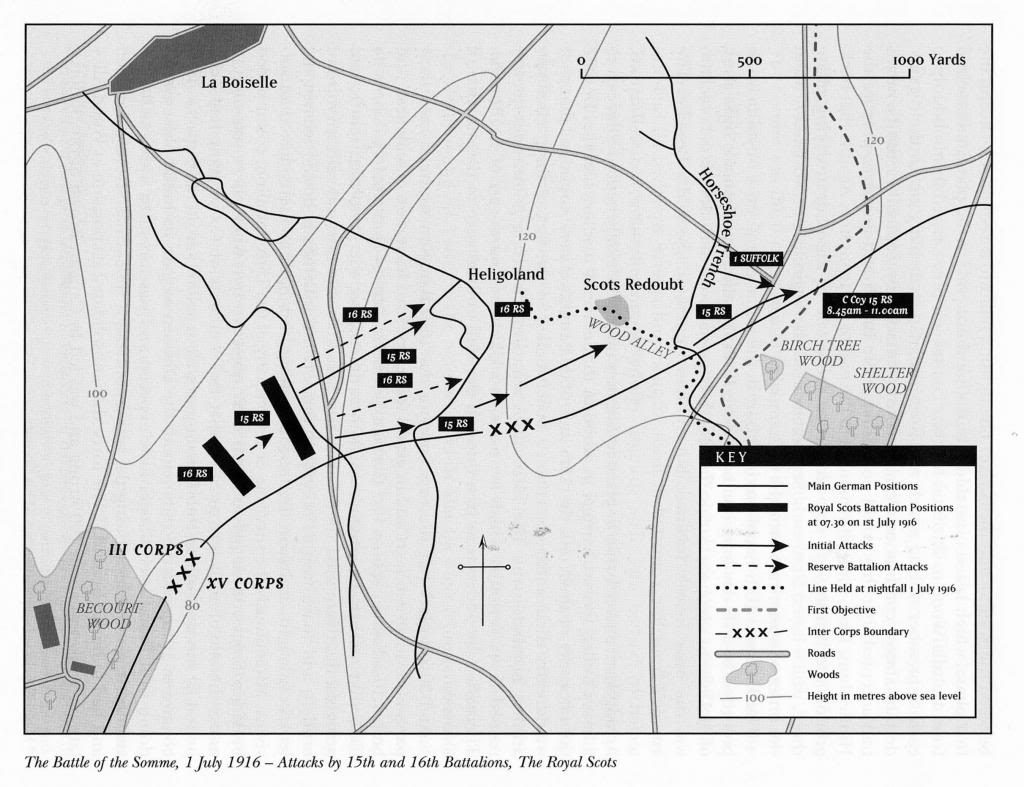

The Battle of the Somme began at 0730 on 1 July when 11 divisions, nine of them New Army, advanced simultaneously against the German positions on the north bank of the River Somme. The 15th and 16th Battalions took part in the initial assault on 1 July on the right flank of the British attack. In doing so they were the only part of the 34th Division, and virtually in the whole of the British offensive, to achieve their initial objective, yet had advanced less than two kilometers. They were relieved on 3 July and went into a rest area until 30 July when, with their casualties replaced, they returned to the front line in the Mametz and High Wood area. They were relieved on 15 August when 34 Division moved out of the Somme sector.

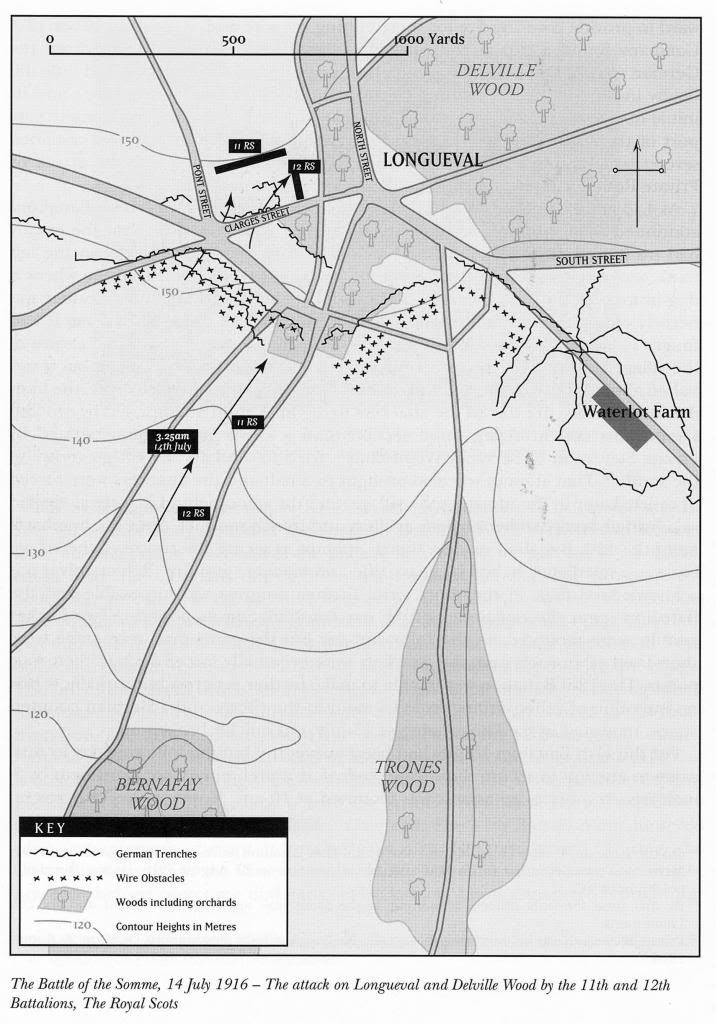

The 11th and 12th Battalions major involvement in July was the attempt to take the village of Longueval at the start of the second phase, which began on 14 July, and lasted, unsuccessfully for the Battalions until the 17th when they were relieved and left the Somme front on 23 July. They returned to the Somme on 10 October and moved into the area area of High Wood, during the third phase, on 19 October where they were involved in actions to secure the feature known as The Butte de Warlencourt. The weather was appalling and everything was a sea of mud leading to large numbers suffering from exposure and trench foot in addition to considerable losses in action. They finally left the Somme sector on 24 October.

The 2nd Battalion’s involvement on the Somme began on 7 July when they arrived in the sector and moved into front line trenches. They were in support to the attack on High Wood on 14 July but not directly involved. On the night of 20/21 July they were committed to the capture of the village of Guillemont which involved them in heavy fighting until relieved on the night of 25/26 July. The Battalion played no further major role on the Somme and left the sector on 23 August.

The 17th Battalion had moved to the Somme sector in early July. Thereafter, together with the rest of 35 Division, it worked ceaselessly in the rear areas providing working and carrying parties to support units in the front line. On more than one occasion it was stood by to play a more direct part in the action but all came to naught. The Division left the Somme on 30 August.

The 9th Battalion, together with the 8th arrived in the Somme sector with the 51st ( (Highland) Division on 20 July. The 9th were deployed in attacking the Mametz/High Wood area from 23-26 July before being relieved. The 8th were deployed throughout in its Pioneer role, which, while not directly involved in the fighting, cost it many casualties. The Division withdrew from the Somme area on 9 August.

The 13th was the last of The Royal Scots Battalions to arrive in the Somme area, reaching it on 21 July. It moved into the Contelmaison area on 9 August and, thereafter, was either manning sectors of the front line or providing working parties until the Division was withdrawn on 4 September to prepare for a major attack on 15 September, the third and final phase of the Somme offensive. The attack, with German resistance worn down over the previous ten weeks, achieved the greatest successes since 1 July with the Battalion capturing Martinpuich and the feature known as ‘Push Trench’. Casualties were still considerable, however, a number as a result of moving too close to our own artillery barrage, but fortunately the percentage killed compared to those wounded or missing was considerably lower than normal. The Battalion was relieved on18 September and, by the time it returned to the front lines in mid-October, the worsening weather was rapidly bringing the campaign to a close. The Battalion remained in the Somme area throughout the winter.

The 15th and 16th Battalions were in the initial assault on 1 July which was preceded by a six-day long bombardment. Both battalions were on the right flank of 34 Division which sat astride the Albert-Bapaume road and their initial objective was the once heavily fortified, but by the now ruined, village of La Boiselle. The enemy’s front line consisted of front, support and reserve trenches, all well protected by barbed wire. The 15th was to advance to a strong point, subsequently named Scots Redoubt, which lay some two kilometres south-east of La Boiselle. Thereafter the 16th was to pass through the 15th and advance to the outskirts of Contalmaison.

At 7.30 am on 1 July the first waves of the 15th Battalion swarmed over their parapets ‘with great heart and in grand form’ and began to advance against the German positions. Almost immediately it became clear that neither the preliminary bombardment, nor four pre-placed mines, had achieved their intended results. The attackers were met with a deadly mixture of artillery and machine-gun fire. They pressed on but soon the long, assaulting lines became mere clusters of survivors. Miraculously the survivors of C Company managed to reach the extreme right of the 15th Battalion’s objective, the German front trench, known as Peake trench, just north of Birch Tree Wood (also known as Peake Wood). They were joined there by survivors of the 16th Battalion as well as soldiers from The Suffolk Regiment, who had been on their left flank. That composite group was the only part of the Division to gain its initial objective. However, in doing so, it found itself dangerously exposed and was forced to withdraw to the vicinity of Wood Alley where, at a strength of around 100, in the overall confusion it seems likely that the Germans were unaware of the tiny pocket of British troops in their midst as no counter-attack was mounted. During the night the force grew in strength as it was joined by other groups which had survived the day’s fighting. Sir George McCrae, Commanding Officer of the 16th Battalion, managed to reach the survivors who then numbered one officer and about 150 men from the 16th, two officers and about 85 men from the 15th and six officers and 60 men from the Lincolns, Suffolks and Northumberland Fusiliers. Additionally the remnants of B Company of the 16th were occupying a trench not far to the rear of Wood Alley. Despite the ferocity of the previous day’s fighting, the troops were in good heart, although they were all thirsty and hungry.

Sir George immediately set about organising the Wood Alley garrison. Food,water and ammunition were carried forward while he made plans to strengthen the position. At about 1 pm the survivors of the 15th Battalion successfully attacked the Germans still holding the Scots Redoubt, capturing 53 prisoners, including three officers. Shortly afterward the survivors of the 16th attacked the Germans occupying a trench known as the ‘Horseshoe’, bombing their way about 150 yards up the trench. At the same time two companies of the 7th East Lancashire Regiment drove the Germans from the strongpoint known as ‘Heligoland’. By the night of 2 July the garrison’s position was much more secure and, importantly, it now had a relatively safe link to the rear. During the night a further 400 reinforcements, drawn from a variety of units, reached the position while carrying parties carried up ample supplies of bombs, water and food, the last including a full supply of hot meat so that all enjoyed a good meal for the first time since the opening of the battle. On 3 July a German counter-attack was beaten off without difficulty and, as a result of having outflanked La Boiselle to the south, that village finally fell to an attack by the 19th Division.

On the evening of 3 July what was left of the 15th and 16th Battalions were relieved and they marched back to Becourt wood. They had been more successful than any other unit in 34 Division yet they had advanced less than two kilometres. The price had been high. The 15th Battalion, who had led the attack, lost 18 officers and 610 soldiers, killed, wounded or missing while the 16th’s figures were 12 officers and 460 soldiers. The losses were such that in the future neither was able to rely solely on recruits from Edinburgh, where both had been raised. For the rest of the war both battalions received drafts from throughout Scotland but, despite that necessity, they retained their special links with Scotland’s capital. For their actions over this period soldiers of the 15th Battalion received immediate awards of a DCM (the RSM) and 7 MMs and three officers received the MC. In the 16th Battalion there were a DCM and three MMs for soldiers and two MCs for officers.

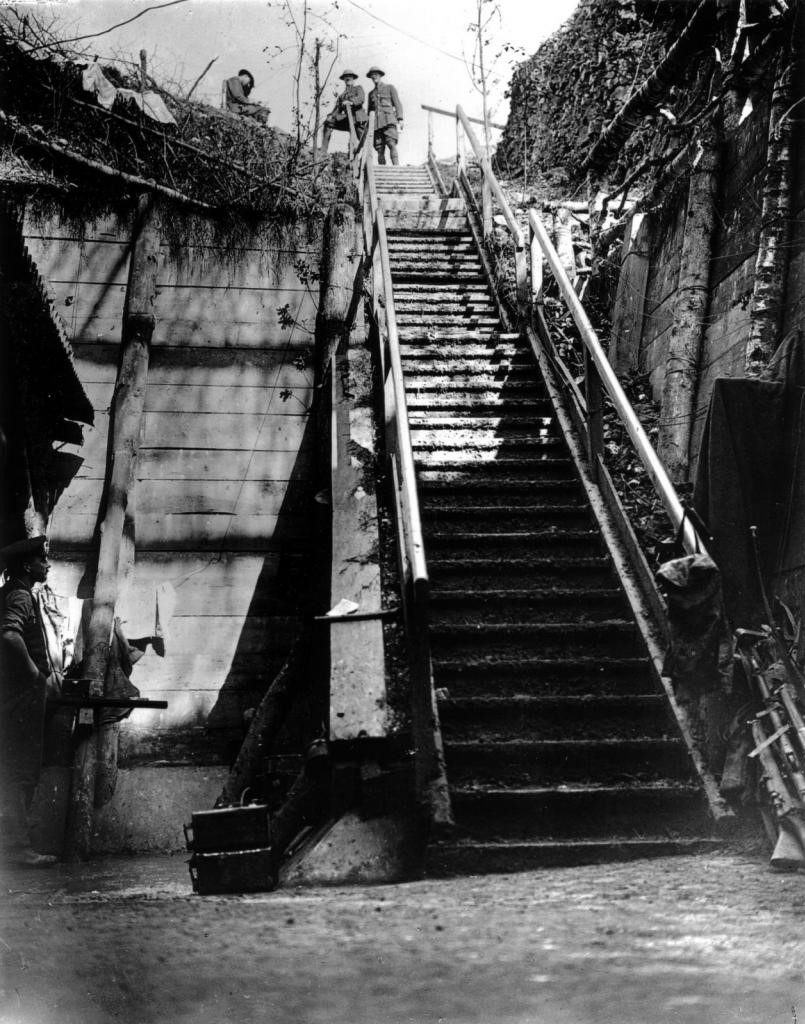

The 11th and 12th Battalions, having moved to the area of Albert in June, were initially hard at work carrying stores of all natures to dumps near the front, but did not participate in the initial assault. On the night of 2 July they moved forward to positions in Montauban. At 9 pm on 3 July the 12th Battalion mounted an attack on Bernafay Wood and, unexpectedly, the Germans withdrew, leaving behind four field guns and one machine gun. Despite that auspicious start, Bernafay Wood proved an unwelcome gain. Regular shelling resulted in numerous casualties. The 12th manned its positions there until 8 July when, together with the 11th Battalion, it was relieved and both battalions marched to the rear for some much needed rest, re-equipment and re-organisation.

German dugout at Bernafay Wood

The next major action for both Battalions was the attempt to take Longueval and the adjacent Delville Wood. These two features were situated on the crest of the plateau and were key positions. If the British could force the Germans out of their well-prepared defences the prospects for being able to continue the advance were good. Inevitably, however, the Germans were equally aware of their significance. The attack began on 14 July. The 11th, together with the 9th Scottish Rifles (Cameronians), were to capture the German trenches in front of Longueval and, thereafter, both Royal Scots Battalions were to seize the village. The operation began with a wholly successful night approach march during which the attackers moved silently into positions some 300 to 500 yards from the German front line. Sadly, however, the Commanding Officer of the 12th Battalion was killed in random shellfire during the move. Our artillery bombardment started at 3.30 am and five minutes later the infantry advanced. The 11th Battalion encountered wire entanglements before it reached the first German trench. During the inevitable delay, while the wire was cut by hand, casualties were heavy. Once the first trench had been secured the Battalion had little difficulty in taking the remaining German trenches forward of the village and its initial objective was secured within the hour. The 12th Battalion, following in support of the 11th, had closed up on it at the German wire. It had also sustained severe casualties and, as a consequence, B Company of the 12th was led into the attack by Private Roden who was awarded the MM for his actions.

At 4.15 am the artillery bombardment lifted from the village and both Battalions continued their advance. It immediately became clear, however, that the enemy had no intention of giving up its hold on the village. The 11th, on the left flank, was able to advance to positions on the western edge of the village where it dug in to await the 12th coming up on its right. The latter’s advance met stiff opposition but, despite losing nearly half of its fighting strength, by 7 am it had fought its way forward to occupy a shallow trench just south-west of the centre of the village. After a brief pause a further attempt to advance was made but it was again halted, 50 yards from the centre of the village, by murderous defensive fire, forcing the attackers to dig in. The 12th made two further attempts that day to secure the village bur with no more success. Reluctantly it was acknowledged that, in the short term, further progress was impossible and the Battalion spent the remainder of the day consolidating its position. The following day, the 15th, two further assaults were mounted but the gains that were made were short-lived as, in each case, the attackers were eventually forced back to their start points. The 12th Battalion was unable to make further progress but, equally, it had no intention of relinquishing its lodgement in the village and a German counter-attack, mounted late in the evening, was quickly broken up.

The ruined village of Longueval

The next day the 11th Battalion attempted to secure the village. Following a preliminary bombardment by Stokes and 2-inch trench mortars an assault was mounted at 10 am. Due to a lack of room for manoeuvre, it had to be carried out by a single platoon. Progress was extraordinary difficult due not only to the German fire but also to wire entanglements and broken trees which were almost impossible to crawl through. After six-and-a-half hours and many casualties, who were replaced individually because it was ‘considered useless sacrifice to throw more platoons into the fight until we had more room to manoeuvre’, the 11th had been no more successful than the 12th. They, however, mounted a final attack on the village at 2 am on 17 July. The night was dark and wet and involved fighting from house to house. Inevitably in these conditions the fighting was confused, and, although progress was made, it subsequently became clear that pockets of Germans had been passed over without being killed or captured. Again the attackers were forced to retire but, despite the confusion, they succeeded in taking their wounded with them.

By late on 17th July, after three days of continuous, close-quarter fighting, much of it in a (once) built-up village area, both Battalions were exhausted and were relieved and withdrew to positions in the rear and then away from the Somme front. The 11th Battalion had lost 13 officers and 308 soldiers while the figures for the 12th were almost identical at 13 and 304. All told, during July 1916, the 11th, 12th, 15th and 16th Battalions had lost over 2000 all ranks killed, wounded or missing.

By the end of July the 15th and 16th Battalions had recovered from their experiences at the beginning of the month. The 15th had received some 500 reinforcements, mostly from other Royal Scots Battalions. They included a draft of 299 from the former 6th Battalion which, together with the 5th Battalion, had moved to France from Egypt in April/May where they merged to form the 5th/6th Battalion and remained as such for the rest of the War. The 16th Battalion had received about 370 reinforcements, including 254 from the 5th and 6th Battalions Scottish Rifles (Cameronians). On 30 July the 15th battalion moved into positions at the north of Mametz Wood while the 16th took up positions to the east of High Wood.

12 RS transport lines in Happy Valley to the west of, and below, High Wood. Some of those watching are wearing captured German helmets and caps.

The latter was sent forward to occupy a trench, half of which, as a consequence of an earlier attack which had only been partially successful, was occupied by Germans held back by a barricade. Determined to evict its unwanted neighbours, D Company mounted five bombing raids along the top of the trench on the night of 1 August but without success. The following night the Company mounted a further assault and, this time, drove the Germans back along the trench for some 150 yards but then had to pull back 30 yards as they had insufficient strength to hold the whole trench. During the following nights both Battalions were involved in further attacks on the German positions, and eventually the Germans were driven out of the location known as the ‘Intermediate Trench’. Thereafter both Battalions occupied positions near High Wood but, on 15 August, 34 Division was relieved and left the Somme for the Armentieres sector.

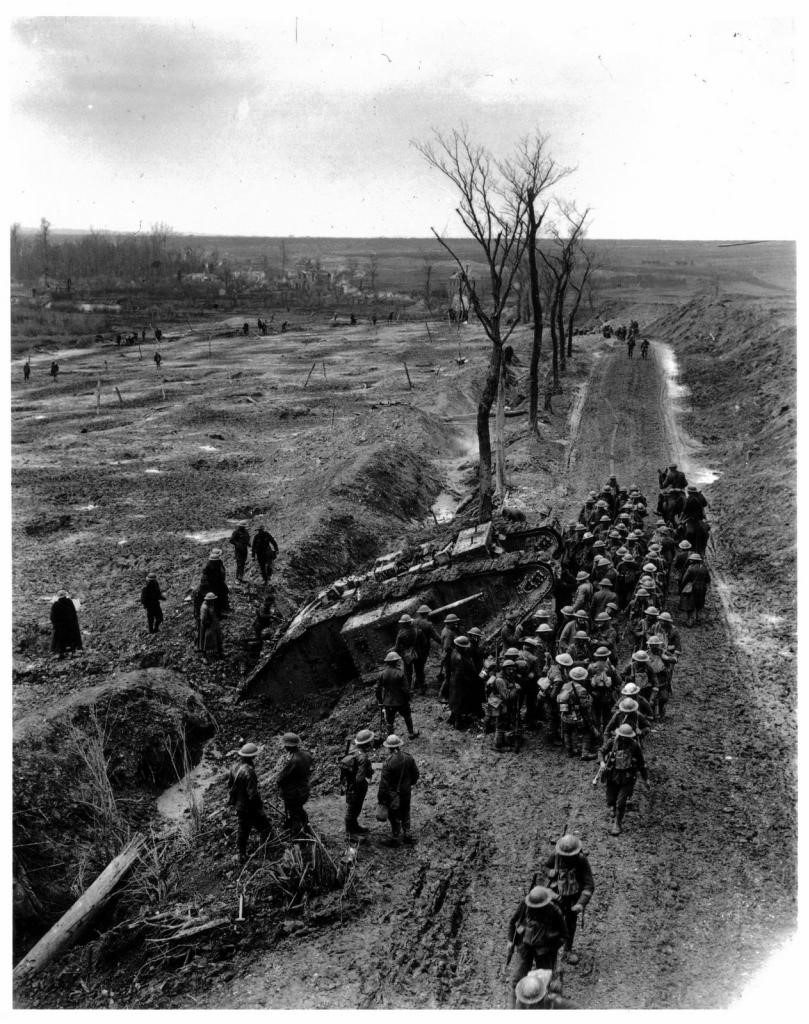

The 13th Battalion, having moved to the Somme area from the Loos salient on 21 July, moved into support positions at Contalmaison on 9 August. Thereafter it was either manning sectors of the front line, or providing working parties, until it was withdrawn to prepare for the assault that was to mark the third, and final, phase of the Somme offensive. The attack was planned for 15 September and the initial objective of the 13th was the German trenches in front of the village of Martinpuich. By then, after over ten weeks of attacks, German resistance was weakening. After a heavy preliminary bombardment, the attack was launched at dawn. Practically no hostile fire was encountered and only token resistance as the enemy was taken by surprise, the 13th did, however, suffer many casualties from our own artillery fire. Nevertheless it speedily seized its initial objective and continued on through Martinpuich to the feature known as the ‘Push Trench’. During the process they captured nearly 200 prisoners including a battalion commander and his adjutant. The War Diary contains the entry ‘At 6 am ‘tanks’ on right and left could be seen advancing.’ marking the first appearance of these, still somewhat unreliable, machines on the battlefield.

A ditched British tank

The gains made on 15 September were the greatest achieved since the offensive opened and marked the turning point of the campaign. Despite weakening German resistance, however casualties, totalling 270, were far from light that day. Thankfully, and for a welcome change, the great majority were wounded, including all nine officers and 143 of the soldiers; 23 further soldiers were killed and 95 were listed as ‘missing’. The Battalion was relieved on 18 September, and by the time it returned to the front in mid-October, the worsening weather was rapidly bringing the campaign to a close.

The 17th Battalion had moved to the Somme sector in early July. Thereafter, together with the rest of 35 Division, it toiled ceaselessly in the rear areas. On more than one occasion it seemed as if it would be called on to play a direct part in the action but its role was confined to the frustrating, albeit essential, task of providing working parties to support units in the front line. At the end of August it left the Somme for the Arras area.

Postscript to the Battle of the Somme.

The detail and, in particular, the scale of casualties in the first phase of the battle, emerged slowly but, when they did, their impact on the Nation was profound. The scale of the tragedy was exacerbated by the composition of the assaulting divisions. They were predominantly composed of the New Army battalions, described by John Terraine in his book The Great War 1914-1919 (Hutchinson, London, 1965, p251) as:

‘The eager, devoted, physical and spiritual elite of the British nation who had answered at Lord Kitchener’s call. The massacre of this breed of men was the price the British paid for the voluntary principle [as opposed to the Continental conscription], the principle of unequal sacrifice.’

There is, however, another aspect of the Somme. The battle lasted for 140 days and, ultimately, it inflicted the first major defeat on the German Army. Despite the horrific casualties sustained on the opening day, and the appalling conditions that had to be endured every day, the British troops, predominantly New Army battalions, displayed the physical and mental stamina that succeeded in grinding down the German Army. The Somme was the British ‘battle of attrition’. Beyond doubt the price was high, but by the time the weather brought the offensive to a close, the Germans knew they could not defeat the British Army. The Somme was the turning point of the war, and it turned on the heroism and stoicism of Kitchener’s New Armies.

By the end of 1916 the New Army battalions had proved their mettle in the bloodiest battle in the history of the British Army. A third, volunteer, army had been superimposed on the pre-war Regular Army and the much expanded Territorial Force. Nevertheless, despite the number and quality of the volunteers for Kitchener’s New Armies, they were insufficient to meet the country’s needs. The introduction of conscription in 1916 would lead, in 1917, to the emergence of a fourth army, where the composition of battalions would be more socially and geographically cosmopolitan. Notwithstanding the impressive achievements of Kitchener’s New Armies in 1916, they did not survive for long as a discreet part of the British Army. The remarkable response to Kitchener’s appeal had, however, been a demonstration of the Nation’s determination to ensure success, whatever the cost.

Casualties

Any discussion of British casualties on the Somme tends to concentrate on the figure of 20,000 killed and some 37,000 wounded on the first day. The casualty level, however, continued at a very high rate, at least into September, rising steeply at the times of major attacks. The figures for The Royal Scots battalions involved in the July battles are given below. They are taken from the individual Battalion’s War Diaries in which the way of presenting the information varies between Battalions. Most, but certainly not all, differentiate between officers and other ranks, killed, wounded and missing, but others, notably the 15th and 16th Battalions, simply group all under ‘casualties’. For the purpose of this exercise all ranks have been grouped together under ‘Killed’ or ‘Wounded/Missing’. Where such division has not been available, such as with the 15th and 16th, the figures have been calculated from an average percentage across those Battalions who provided a breakdown.

| Battalion | Killed | Wounded/Missing | Total Casualties |

| 2 RS | 79 | 335 | 414 |

| 8 RS | 19 | 130 | 149 (A Pioneer Battalion) |

| 9 RS | 26 | 186 | 212 |

| 11 RS | 85 | 399 | 484 |

| 12 RS | 104 | 403 | 507 |

| 15 RS | 111 | 517 | 628 |

| 16 RS | 84 | 388 | 472* |

| Totals | 508 | 2358 | 2866 |

*To put the above figures into context, 16 RS crossed the start line on 1 July at a strength of 810 All Ranks. By 3 July they had suffered 472 (58%) casualties.

Other significant casualty figures during the campaign were:

| 2 RS (August) | 13 | 82 | 95 |

| 11 RS (October) | 21 | 141 | 162 |

| 13 RS (September) | 32 | 278 | 310 |

| (October) | 13 | 64 | 77 |

| 17 RS (October) | 18 | 134 | 152 |

| Totals | 97 | 699 | 796 |

| Grand Totals | 605 | 3057 | 3662 |

Postscipt

This Grand Totals of casualties are ‘not less than’ figures and, taking the 810 strength figure of 16 RS on 1 July would equate to the total loss as casualties of four and a half out of the nine, or just over half, of the total strength of The Royal Scots Battalions committed to the Somme. One result of these losses in such a short time was that the Regiment was no longer able to rely solely on reinforcements recruited from the Edinburgh area. For the rest of the War such reinforcements generally, but not always, came from across Scotland.

During the 1st World War The Royal Scots raised 35 Battalions. Over 100,000 men served in the Regiment of who 11,213 were killed and over 40,000 wounded, a casualty rate of over 50%. The 3662 casualties shown for the Somme, in only 3 months, represent 7.2% of the total casualties in 5.9% of the length (51 months) of the War. That total does not, however, include all the Regiment’s casualties in France or those in other theatres. The total of casualties over the period was, therefore, significantly above the average throughout the War. A further difference was that so many occurred amongst the Battalions of the ‘New Armies’ raised from the volunteers of 1914 and early 1915 rather than amongst pre-War regulars and territorials. The losses were, therefore, spread much more into every area and street of the Country, though often, as a result of ‘the Pals’ Battalions, concentrated into very small areas.