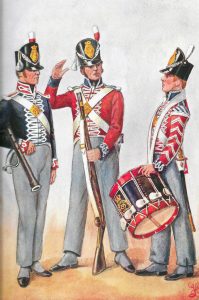

Members of the 3rd Battalion 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment of Foot

at the time they were raised in 1803

Bandsman, Private (Battalion Company)

and Drummer (Grenadier Company)

as at The Battle of Waterloo

“It was a dreadful day and night of thunder and rain, and the army having no shelter suffered much. The morning of the 18th cleared and the sun dried the ground a little, but we were still ankle deep in the mire”. Operations of Picton’s Division’ attributed to Ensign Mudie

“We took off our coats and shirts and rung them like the Washerwomen …the water ran off the sleeves like a shoot at the side of a house in England.”

Lt John Lewis Black’s letter to his Aunt 11 Jul 1815

“About eight they began to cannonade … the shells and balls were like the hail when it rains and hails too at the same time it comes in flakes so the shell and balls a dozen for one minute then stop then another. About ten they began to send down their Columns – they were so thick that for two miles from Right to Left you could not see the ground.”

Lt John Lewis Black

“the thunder of such a number of cannon was tremendous, while masses of cavalry rushing forward to force the adamantine squares, fell in heaps beneath the British fire, though their pigeon-breasted armour” was of use if struck in a slanting direction, but where the well rammed ball struck fair through it went.” ‘Douglas on the Peninsula’ by John Douglas

“Our squares at the commencement of the action were placed on the face of the hill and were completely exposed to the shot of the enemy which did great execution. Wellington to remedy this retired us a little over the crest of the hill which caused the guns to be in advance while we were less exposed, During repeated charges of cavalry the Artillery men had often to take shelter in the squares, while some lay under the guns to save themselves from the lances.”

John Douglas

“…the battle of the 18th opened my eyes. I found our division about 4500 to 5000 strong, stemming the torrent of attack against a body triple its number: they were assisted by Brunswick troops, but we had no British cavalry, and scarcely any artillery, but had to trust entirely to the bayonet and musketry fire.”

Ensign Charles Mudie

“The slaughter was great on both sides, and would have been greater but for the ground being so soft the balls which struck it never rose again.”

John Douglas

“Quartermaster Griffiths, whose proper place was the baggage in the rear, hearing of our last officer, B. Major MacDonald being badly wounded, came galloping into the square: ‘Griffiths’ cries McDonald ‘you must take the Command’.

‘Yes’, says he, drawing his sword, ‘TWO years ago I was a private in the Royals, and now I command the 3rd Batt in the field, sitting on horseback staring at the enemy’. ‘Dismount Griffiths’ Macdonald, ‘you’ll be killed’. ‘Never heid’ was the cool reply, ‘a ball will kill me on foot as well as on horseback’

John Douglas

“The Commissary arrived with the ration liquor and out of a Company 100 strong on the morning of the 16 Eleven now sat round to drink, not the health, but the memory of those who had vacated their places in the ranks.”

John Douglas

The wounded of both sides were in a piteous state, desperate for a doctor or a drink of water. I tried to assure them they would be taken care of, and our party commenced digging a grave for a fine young fellow of ours who had fallen close by them. The marauders had been up earlier than we – the body was stripped naked. When about to put the earth over it a Scotch soldier took from his breast pocket a Prayer-book, and put it into my hands without saying a word.

There are moments in which even the stoutest hearted of us all are made to feel. The funeral service was read,…our wounded soldiers sat up and listened with the most revered attention. The French raised themselves on their elbows and gazed at us with astonishment. The whole scene, together with the beautiful language of the Liturgy, was calculated to produce the highest effect – “In the midst of life we are in death.”

1 Around 4am in the morning the breast pieces of the Cuirassiers were used ‘for frying pans’. “I ate some very good collops* cooked in that way” (*traditional Scottish meat dish) Ensign Mudie

2 Before Badajoz an altercation between QM Griffiths and the QM of 38th in respect of rations resulted in Griffiths being confined, tried and reduced to a private. However when Edward, The Duke of Kent ‘our Colonel’, heard of it he sent out orders for his restoration. John Douglas

Ensign Grant Stuart Kennedy “…was carrying a Colour in advance of the Battalion and was shot in the arm but continued to carry it until he was again shot but this time killed or mortally wounded. A Sergeant then attempted to take the Colour from his hand but could not disengage his grip, so he threw the body over his shoulders and rejoined the ranks of his Battalion only through the chivalrous notion of the Officer Commanding the French Battalion opposed to The Royals, who ordered his men not to fire on the Sergeant and his burden.” Kennedy was 15 years old sadly the name of the Sargent is not reconised.

Sergeant Major Francis Quicke (RSM) also carried a Colour but, in doing so was later shot through the heart and died.

He was 5 feet 10 inches in height and 28 years of age when he joined the 3rd Battalion, with a fresh complexion, grey eyes, light hair and a long face. He came from Somerset, the parish of Bushford, his trade ‘Labourer’. He transferred from the 28th Foot at Fermoy, Ireland.

Sergeant Major Quicke is remembered on the marble slab at St Joseph’s Church, Waterloo, alongside Kennedy and the other men and officers that died in the Waterloo campaign. There are many stories that tell of Ensign Kennedy, but rarely named is the Sergeant who carried his body which still grasped The King’s Colour.

Ensign Richard Blacklin, born 1790 County Durham, was a Navy Midshipman before he joined the Militia in Ireland. He volunteered for Foreign Service following Napoleon’s escape from Elba 26 Feb 1815. Armed with an introduction from HRH the Duke of Kent, he joined the 3rd Battalion at Fermoy Mar 1815. As his commission was dated 18 Jul, he fought at Waterloo as a Volunteer, in the Colour Party, in the thick of the fighting. In the early afternoon Pack’s Brigade took the full force of the attack by 3 infantry Divisions of the French 1st Corps, 14,000 strong, commanded by D’Erlon.

Successive charges by heavily armed French cavalry forced the British regiments to form square, while under heavy fire from French artillery and tirailleurs. These assaults, together with the loss late afternoon of La Haye Sainte, left Wellington’s forces in a critical condition. The arrival of the Prussians from the East relieved the pressure and Napoleon ordered the Garde Imperiale to attack Wellington’s position. This attack, the only encounter between French and British Foot Guards in the Napoleonic Wars, was narrowly beaten off, and the headlong retreat of the French Guard “La Garde recule!” about 8pm, marked in effect the Allied victory.

Ensign Blacklin carried the King’s Colour after 4 officers had been killed, and was himself wounded, apparently by a shell splinter in the shoulder. He was one of 5 officers out of 39 who marched with the Regiment to Paris, 34 having fallen, killed or wounded at the battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo. Captain Macdonald, who took command after Major Colin Campbell was wounded, later wrote “during the most trying part of the action, I particularly observed Lieut. Blacklin’s activity and zealous exertions for the good of the Service”.

By 1839 he was the last serving officer of the Regiment who had been at Waterloo. A staff officer in the Crimean War, Colonel in 1858, he became a Military Knight of Windsor 1865. He was buried in 1867 in St George’s Chapel with full military honours. Of 7 sons and 4 daughters, his son Frederick followed him into the Army, dying of yellow fever in Belize 1868.

Ensign William Thomas joined without purchase 15 Dec 1814. One of only two Ensigns out of 10, left standing by the end of Waterloo, with 3 killed and 5 wounded. Afterwards he marched to Paris with his Bn as part the army of occupation. After joining the 2nd Bn in India he was wounded in May 1818 at the ‘Siege and Storm of Malligaum’. Becoming Lieutenant in Apr 1820, he died serving on the Island of Dominica 15th July 1833.

Ensign Charles Mudie born Arbroath 3 Aug 1784, was a married merchant/soap-boiler, and Lieutenant in the Forfarshire Militia. On 4 Nov 1813 he commissioned as Ensign into the 3rd Battalion and was sent to the Peninsular War. When the Waterloo campaign started, his battalion embarked at Cork, Ireland on 5 May 1815, to arrive in Ostend on the 17th. On 15 Jun, brigaded with 42nd,44th and 92nd Regiments under General Pack, forming part of Sir Thomas Picton’s 5th Division. Ensign Mudie was present at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, one of four officers left. Severely wounded, he received one year’s pay and a pension of £50 for life. He accompanied his battalion in their march to Paris on 7 Jul 1815. “Of the four officers who commanded my regiment successively on 16th and 18th of June, three have since paid the debt to nature and one is crippled for life. Of those…officers who came out of the field unharmed, two only survive; four or five of the wounded are since dead and four disabled. As to the rest, the Government got rid of them as fast as they could. Many had served through all the Peninsular War, and were turned adrift, some on 4 shillings, some on 3 shillings a day, and the Minister of the day denounced them as a “dead weight” on the country, instead of having them brought back to employment, and thus relieving the country of the expense of half-pay.” Captain Mudie died on 29 Jun 1841 from dysentery.

Sergeant John Douglas, born Lurgan, Ireland, 1786, was a Weaver when he joined the 1st Foot in 1809. He was 18, 5ft 5 ½, with a fresh complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. Promoted to Corporal on 10 Dec 1811, he became Sergeant on 25 Dec 1814. His memoires “Douglas on the Peninsula 1809-1817” give a vivid depiction of Army Life. He was awarded the Waterloo Medal and Military General Service Medal with 7 clasps for Busaco, Fuentes D’onor, Salamanca, Vittoria, St Sebastian, Nivelle and Nive. Having suffered injury to his right leg he became an ‘out pensioner’ of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham. He married in 1823, had 17 children and died in 1866 aged 79. This c.1860 photograph is said to represent him. However this gentleman has three medals. It is possible John was awarded another whilst serving as an Army Volunteer staff member at the Royal Hibernian Military School in Dublin. His children attended the school and his son John George joined the 84th Regiment, becoming orderly Sergeant. This is the only known photograph of a member of the Regiment that served at Waterloo.

John Samuel, born Carmarthen 1792, enlisted Sept 1811, was wounded by a musket ball in the breast at St Sebastian 25 Jul 1813. On 16 Jun 1815 at 3pm Sir Thomas Picton stopped the French advance. French cavalry attacked and Private John Samuel was wounded by a musket ball in the right knee. Picton was killed by a bullet to the head. During the battle he had worn a dark frock coat and a top hat. John survived, made Corporal Jan 1825, and last appeared on the Musters 11 Nov 1825.

Richard Harvey born 1783 Horsley, one of 7 children, enlisted age 24 on 25 Aug 1807, at Malden. His son Richard was born on an army transport ship on the way to Waterloo. A private in Capt James Cowell’s Coy No 1 he was discharged 3 Apr 1817 Canterbury, after 11 years & 283 days of service – his conduct “good”, the reason for discharge “being worn out in the Service”. He is described as 5ft 5inches, with brown hair, grey eyes and a fresh complexion, trade Labourer. The papers have his mark, as he was illiterate. Returning home he remarried 1825 and died 1845 aged 62. His son married twice, had 15 children and worked as a stoker at Battersea Gas Works, dying Christmas 1889 aged 74.

Matthew Andrews enlisted Edinburgh Oct 1807 for a bounty of 11 guineas. Transferred from 4th to 3rd Battalion in Portugal Jun 1810. Awarded the Military General Service Medal for the Peninsula War, with bars for Vittoria, St Sebastian, Nive and Nivelles, the Battalion returned to Ireland Aug 1814. After 7 years he re-enlisted for £5 8s 4d. Surviving Quatre Bras and Waterloo unscathed, when the Battalion was reduced on 24 Apr 1817 Chatham, he joined 1st Battalion in Ireland. Discharged Jul 1827 Stirling after 19 years 295 days “in consequence of length of service and worn out” he left with a wife, 2 small children and £1 (20 days pay), 12s,10½ p and a pension of 1s a day. Settled Airdrie, an Iron Works labourer, he died in May 1853.

James Springthorpe, born in the Parish of Sleaford near the town of Lincoln 11 Jul 1790, enlisted in Nottingham District. Aged 18 years, 5ft 7 inches, with a fresh complexion, grey eyes, light brown hair and a round face, he attested (before a magistrate) on 18 May 1807 into 1st Foot (The Royal Scots).

He appears on the muster rolls Sep-Dec 1807 in the 4th Battalion, based Edinburgh Castle. Transferring to 3rd Battalion on 25 Dec 1807 he went to Portugal for the Peninsula War. Returning to Cork 25 Sep 1813, Fermoy 1814, and after being wounded at Waterloo to the UK on 9 Jul 1815, and 26 days in hospital. He joined 1st Battalion 8 Jul 1815 at Edinburgh Castle, and then 3rd Garrison Battalion 25 Dec 1815 in Chatham. Discharged on 9 Jan 1816 his papers state he is 26 years 5ft 6¾ (he lost ¼ inch) with dark brown hair and hazle eyes. Wounded at Waterloo (gunshot wounds to right hand and shoulder) whilst serving with Capt Thomas Moss’s Coy No 3, he was rendered ‘unfit for further service’ and became a Chelsea ‘out pensioner’. He married twice, had children and died July 1849, aged 59 years. He was awarded the Military General Service Medal 1793-1814 with 4 clasps for Corunna, Salamanca, Vittoria and San Sebastian. Despite his medal being returned to Horse Guards in 1816, he must have reapplied for it later because his medal was brought into the Museum by a private collector, where James’s descendant, also James Springthorpe, was able to view it.

Captain James Springthorpe was born in Edinburgh c1940s and joined The Royal Scots (The Royal Regiment) aged 16. He rose through the ranks to become a Captain. On retiring he became The Royal Scots Benevolence Secretary and Regimental Administrator. He attended the Unveiling of the Waterloo Colours in The Royal Scots Museum where he met the descendant of Lt Richard Blacklin, Sir Christopher Bellamy.

Our researchers have traced the line down through the Springthorpe descendants, some became miners and others emigrated. The Regiment has a strong tradition that all who are born into the family of a serving solider or officer are part of its family – sometimes for generations.